The Eighth Commandment—“Thou shalt not steal”—sanctions property rights, but Psalm 24:1-2 declares that the Lord holds clear title to all there is, and that our ownership is both contingent upon his good pleasure and accountable to his principle of stewardship:

The earth is the Lord’s, and the fullness thereof;

The world, and they that dwell therein.

For he hath founded it upon the seas,

And established it upon the floods. [1]

Earth and World

Verse one employs two Hebrew words to express the extent of God’s reign, the first, aretz (‘earth’), denotes material resources; the second, tebel (‘world’), connects the earth to human enterprise. The Septuagint tracks with this, using gefor ‘earth’ (hence, ‘geology’) and oikoumene for ‘world’ (connected with ‘ecumenical’). Thus, the span of God’s provision and sovereignty is beneficently universal.

Citing Ecclesiastes 1:4, Gregory of Nyssa observes that the earth ministers “to every generation, first one, then another, that is born on it.” [2] Matthew unpacks the extent of the earth’s “ministry,” saying,

The mines that are lodged in the bowels of it, even the richest, the fruits it produces, all the beasts of the forest and the cattle upon a thousand hills, our lands and houses, and all the improvements that are made of this earth by the skill and industry of man, are all his. . . . All the parts and regions of the earth are the Lord’s, all under his eye, all in his hand: so that wherever a child of God goes, he may comfort himself with this, that he does not go off his Father’s ground.[3]

Spurgeon speaks of its “fullness” in terms of “its harvests, its wealth, its life, or its worship; in all these senses the Most High God is Possessor of all.”[4] And Derek Kidner says the word “conjures up its wealth and fertility, seen here not as man’s for exploitation, but, prior to that, as God’s, for his satisfaction and glory . . .”[5]

“Ride, Jesus, Ride!”

Of course, materialists beg to differ (yea proudly insist upon differing). By their lights (or rather from their gloom), they deny the artistry, authority, and generosity of God in creation. They fail or refuse to grasp the obvious truth that God supplied graciously arable soil, fishable waters, and huntable woods; flax, wool, and cotton for weaving; timber and gypsum for building; metals for machinery; fossil fuels for heating and transportation; organic compounds for medicine and palliation—salicin from the willow, quinine from the cinchona, and codeine from the opium poppy. On and on the provision extends. And, of course, it extends to the human ingenuity required to marshal these resources for our benefit.

As poet Gerald Manley Hopkins observed, “The world is charged with the grandeur of God,” [6] and blessed in the sensible person who notes it. Back in the 1970s, I heard, in a Wheaton College chapel message by E. V. Hill, who described a parishioner who was ever so aware of God’s magnificent immanence. Hill told of his own boyhood congregation’s response when tornado warnings came their way down in Texas. The church had a big basement, and the flock would rush to gather there until the winds subsided. But one time, after counting noses, they discovered that “the Old Widder Jones” was missing, so some hearty volunteers jumped into a buckboard and raced to her house. When they got there, they found the home creaking in the wind with the windows wide open, the curtains blowing straight out on one side and straight in on the other. Flinging open the door, they spied her across the room, rocking furiously in her favorite chair, exclaiming, “Ride, Jesus, ride!”

I hasten to say I’m writing this the week after a horrific tornado leveled Mayfield, Kentucky, killing dozens there and elsewhere in its path. So I don’t want to suggest that Jesus initiated the ruination—and, as some might suggest, as an act of judgment on that community. (Eliphaz, Bildad, and Zophar went down this road shamefully in Job.) But Mrs. Jones had it right when she recognized the sovereignty of God in all Creation, not just at the outset, but throughout its every age. And so should we. (Yes, I know about the Problem of Evil; I’ve taught whole courses on it; but here I appeal to the “Soul-Making Theodicy”—which argues that the rigors and perils of life after the Fall are perfectly ordered for God’s saving and sanctifying purposes.)

The Lord’s Aesthetic Purposes

We’ve noted the nutritional and industrial provisions of the earth, but we must also give the Lord’s artistry its due. In Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, Annie Dillard tells of a practice she had as a little girl, back when a penny meant a lot to her. She would hide one of these coins among exposed tree roots and other notches and then write in chalk on the sidewalk just up the way, “Surprise Ahead,” with arrows leading to the treasure. She then observed that those who would take time to humble themselves and slow down to search out the beautiful in nature would be rewarded, for “the world is fairly studded and strewn with pennies cast broadside from a generous hand.” [7]

Well, as we know, the Lord has not only strewn pennies in the form of a “tremulous ripple thrill on the water” signaling the emergence of “a muskrat kit paddling from its den” (Dillard’s example), but also the golden coins, indeed ingots of precious aesthetic “metal,” appearing around the world. These manifestations have inspired poets and composers as well as painters and photographers. Thus we are witness to Henry Wadworth Longfellow’s A Day of Sunshine, Carl Sandburg’s Fog, Edgar Guest’s It’s September, and to countless celebrations of nature from the likes of Frost, Wordsworth, Keats, Kipling, Blake, Tennyson, Nash, and Burns. As for picturesque program music, we enjoy Claude Debussy’s orchestral piece La Mer, Ferde Grofés’ Grand Canyon Suite, Bedrich Smetana’s symphonic poem, The Moldau, and Antonio Vivaldi’s violin concertos, The Four Seasons.

As for paintings, let’s focus on a small sampling of four that suggest themselves upon a reading of Psalm 24.

Young Hare (1502), Albrecht Dürer, The Albertina Museum, Vienna, Austria.

Dürer was a contemporary of his fellow German, Martin Luther, and though the artist’s roots were Catholic, he showed sympathy for the Reformer’s cause. Though a great many of his works dealt with religious themes, including the oft-reproduced Praying Hands, he also had an eye for nature, as with this painting of a rabbit and also in his woodcut, The Rhinoceros, which he drew without having ever seen one, working only from a verbal description and another’s brief sketch.

When the words ‘earth,’ ‘world,’ and ‘fullness’ are deployed, we typically think of matters on the grand scale—the Great Plains, the Alps, the Everglades, the Gulf Stream, the Sahara, the Amazon Rainforest. But God has filled these great sectors with equally amazing, diminutive critters, such as this hare. And for those who would demean man as an insignificant creature on a small planet in an unfathomably vast universe, C. S. Lewis replies, “[T]he argument from size, is in my opinion, very feeble”; [8] size is irrelevant to honor, for a tiny, sapient man, who alone among sentient beings has the power to appreciate the “the great nebula in Andromeda,” is more wonderful than the stupendous astronomical displays he’s appreciating.[9]

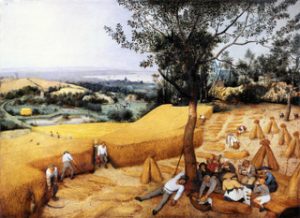

The Harvesters (1565), Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, New York

Bruegel was a leading artist of the Dutch-Flemish Renaissance. This particular painting was commissioned by a Belgian merchant, one of six works representing human activity in the progression of seasons, this one focused on late summer. (Another well-known piece in this cycle is The Hunters in the Snow.) Though Bruegel painted religious subjects, such as The Fall of Rebel Angels, The Blind Leading the Blind, and The Census at Bethlehem, he was best known for his “genre paintings” of peasants. I should add that this was a time of great religious tension in Europe, as Bruegel was born just eight years after Martin Luther penned his Ninety-Five Theses.

The Harvesters records and honors both man and nature—the golden sea of wheat, crisply delineated by scythes, instruments of human ingenuity with ergonomic handles and blades the deliverance of metallurgy; the fellowship and refreshment of lunchtime, including a loaf a bread, whose substance comes from such sheaves as stand all around; the mercies of shade and a nap; and a vista easy on the eyes. It’s enough to send an artist looking for his brushes and easel.

[1] I use KJV here since the lyric quality of the iambic tetrameter in the first verse (which the RSV and ESV preserve) is lost in, for example, in such estimable translations as the NIV (“. . . with everything in it . . . and all who live in it”), the HCSB (“ . . . and its inhabitants”), and the NASB (“ . . . and those who live in it”). Of course, all of them report accurately that the Psalmist celebrated the comprehensive authorship and disposition of the cosmos and its occupants.

[2] Gregory of Nyssa, “Exposition of the Psalms 24:2,” quoted in Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture, Old Testament VII, Psalms 1-50, edited by Craig A. Blaising and Carmen S. Hardin, Thomas C. Oden, general editor (Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity, 2008), 185

[3] Matthew Henry, Matthew Henry’s Commentary on the Whole Bible, Vol. III—Job to Song of Solomon (New York: Fleming H. Revell, 1975 ) 319.

[4] C. H. Spurgeon, The Treasury of David, Volume I (Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson, 1990), 374.

[5] Derek Kidner, Psalms 1-72: An Introduction & Commentary (Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity, 1973), 113.

[6] Gerald Manley Hopkins, “God’s Grandeur.” Accessed January 5, 2022 at https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44395/gods-grandeur.

[7] Annie Dillard, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek (New York: Harper & Row, 1974), 14-15.

[8] C. S. Lewis, “Dogma and the Universe,” God in the Dock (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1970), 39.

[9] Lewis, “Dogma,” 41-42.