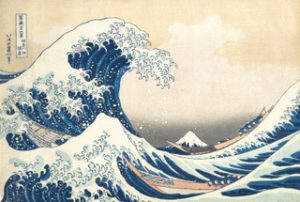

The Great Wave Off Kanagawa (1831), Katsushika Hokusai, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, New York

Featured in Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji, this woodblock print captures the peril of three fishing boats tossed by a rogue wave in Sagami Bay, twenty-five miles southwest of Tokyo. In the year this painting appeared, 1831, another great outdoor painter, John James Audubon, traveled from England to New York to begin his work on Birds in America; Meanwhile, over in Europe, the Impressionist artists, Monet and Renoir were still children, but they would one day be influenced by Hokusai’s work.

There is much beauty in nature, but aestheticians have identified an experience that goes beyond savoring a sunset, delighting in a blanketing snowfall, or taking in the fall colors of New England. They speak of “the sublime,” that which is intimidatingly splendid. It’s kin to a word occurring five times Psalm 24:7-10—‘glory,’ as in “the King of glory.” The Hebrew word for ‘glory’ is kabod, a cognate of kebed (“heavy”); it connotes substance and heft, the sort of awesome presence that terrified Isaiah in his chapter six. Painfully aware of his deplorable weakness, the prophet feared being “crushed” by the sovereign holiness of God.

The eighteenth-century British philosopher and statesman Edmund Burke, in speaking of the sublime, identified it as “astonishment,” that is the “state of the soul, in which all its motions are suspended, with some degree of horror. In this case the mind is so entirely filled with its object, that it cannot entertain any other.” And, for illustration, he pointed to the ocean, which can be “an object of no small terror.” [1]

In his Critique of Judgment, Immanuel Kant supplied other examples of the sublime:

Bold, overhanging, and, as it were, threatening rocks, thunderclouds piled up the vault of heaven, borne along with flashes and peals, volcanoes in all their violence of destruction, hurricanes leaving desolation in their track, the boundless ocean rising with rebellious force, the high waterfall of some mighty river, and the like, make our power of resistance of trifling moment in comparison with their might.[2]

And so we’re pointed to the oceans, whose water covers around seventy per cent of the earth and whose dynamics are quite sublime, as Hokusai knew full well.

This painting hails from the Far East, in contrast with the other three, which are Western. I include it to underscore the gospel implications for lands unknown to (even unsuspected by) the Israelites in David’s day. Though Psalm 24 is Hebrew scripture delivered to God’s chosen people, its reach circles the globe. As Augustine observed of Psalm 24:1-2, “This is true, for the Lord, now glorified, is preached to all nations to bring them to faith, and the whole world thus becomes his church.” [3]

The Domes of the Yosemite (1867), Albert Bierstadt, The Athenaeum, St. Johnsbury, Vermont

Psalm 24:1-2 – 1The earth is the Lord’s, and the fulness thereof; the world, and they that dwell therein. 2 For he hath founded it upon the seas, and established it upon the floods.

Bierstadt, an eighteenth-century German-American painter was remarkable for his glorious landscapes, as were other Americans of the Hudson River School—Frederick Church, Asher Durand, George Inness, Thomas Cole, Thomas Moran, and Thomas Cole. Whether working in the Hudson Valley, the Sierra Nevadas, Yellowstone, or the Andes, these men astonished their viewers with breathtaking portrayals of God’s handiwork. Bierstadt introduced many to the Rockies, helped spur the conservation movement, and has been featured on two of America’s commemorative stamps.

This painting portrays California’s Yosemite Valley, granted protection under Abraham Lincoln in 1864 and designated a National Park in 1890. Though romanticized, Bierstadt’s rendering is nonetheless indicative of the grandeur of this site, a reality well chronicled in a series of black and white photographs by Ansel Adams, whose work is featured in a Yosemite Village gallery.

Psalm 24:2 encompasses the granite domes that define the valley, for it says the Lord founded the earth “on the seas and established it on the waters.” Well, certainly, Genesis 1 says that the waters were gathered so that the dry land would appear on the third day of creation, but young-earth creationists point beyond this to Psalm 104, where we read, in verses 5-8:

Who laid the foundations of the earth, that it should not be removed for ever.Thou coveredst it with the deep as with a garment: the waters stood above the mountains. At thy rebuke they fled; at the voice of thy thunder they hasted away. They go up by the mountains; they go down by the valleys unto the place which thou hast founded for them. Thou hast set a bound that they may not pass over; that they turn not again to cover the earth.

They read Noah’s Flood into this passage, for “turn not again [ever] to cover the earth” would not make sense if the psalmist were speaking only of the initial emergence of land. It would ignore the subsequent, universal immersion above the tallest mountains recounted in Genesis 7.

Beware of (and thank God for) Wadi Rum.

Worldview-wise, there are two big ways of seeing our surroundings. One is naturalistic/materialistic, regarding flora and fauna, hill and dale, you and me, as the product of chemical and physical laws at work on some sort of primordial stuff. On this model, it would take eons of dumb matter talking to itself (“dialectical materialism”), through hit or miss, to generate Handel’s Messiah. It’s hard to believe that folks would embrace such “seeing,” given its Rube Goldberg absurdity, but they soldier on, determined to keep God’s hands off the universe.

The other view regards the universe and all within as the handiwork of a multi-omni creator. Some have proffered various versions of the Anthropic Argument for God’s Existence, working from the wonderful correspondence of man’s needs to the Lord’s earthly provision, the way that the environment is marvelously attuned to our makeup, e.g., the right mix of the gases we breathe; the distance to the sun and tilt of the earth, giving us tolerable seasons. Of course, the Darwinists counter that it fits us since we fit it; if we didn’t, we’d be extinct. They venture a deflating analogy, that of the woman who marveled that God had caused great rivers—the Thames, Tiber, Seine, and Danube—to flow through the capitals of Europe.

This snappy dismissal of the wondrous correspondence between Creation and her creatures’ blessings does not bear up to scrutiny, and the aesthetic provisions of nature are particularly troublesome for the materialist. (Indeed, the problem cropped up early on, when eighteenth-century art critic John Ruskin pressed Charles Darwin to explain the glories of a peacock’s deployed fan.) Darwinian philosopher Denis Dutton gave it his best shot in The Art Instinct: Beauty, Pleasure, and Human Evolution, when he played off a worldwide affinity for “blue landscapes” (with a stream winding its way through a verdant, populated valley).[4] He reasoned that this was the product of natural selection, in that creatures who migrated there more likely survived and procreated, and thus passed along their aesthetic wiring to progeny evolving through natural selection.

But this fails to explain our aesthetic appreciation for deadly settings, such as lightning storms, a cluster of icebergs, and desert regions, such as Wadi Rum in the south of Jordan, an extension of Israel’s Negev. In my experience, Wadi Rum is one of the most visually enchanting places on earth. Yet, the hot, red sands under a relentless sun can make even shoe-clad walking miserable, and the expanse of desolation, replete with shear granite outcroppings, would make one despair of survival if not for the air-conditioned tour bus standing nearby.

Filmmakers have used it in Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker, Dune, and The Martian, whose star, Matt Damon, remarked, “I was in awe of that place . . . One of the most spectacular and beautiful places I have ever seen, and like nothing I’ve ever seen anywhere else on Earth.” [5] But how could it be beautiful? What sort of survival-of-the-fittest story could one concoct to explain the development of an appetite for deadly landscapes?

I’m sure that Darwinians could come up with something. Actually, they have to do this, given their devotion to “methodological naturalism,” conveniently overlaying their metaphysical materialism. (Harvard biologist Richard Lewontin wrote that, no matter how contrived the scientific theories might seem, they had to stick with purely material accounts, lest a disruptive “divine foot” find its way in the doorway.) [6] Besides, nothing is foolproof since fools are so ingenious. Perhaps they can argue that the terrain is so awful that it’s a good place to hide out and have kids since no one wants to bother you there. Well, “Whatever,” and “Knock yourself out.” But far better to say that the “fullness thereof” includes not just the nutritional, hospitable, and industrially harnessable, but also the aesthetical, thanks to God’s astonishing kindness to the world’s inhabitants, to “those who dwell therein.”

[1] Edmund Burke, “Of the Passion Caused by the Sublime,” A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, Harvard Classics, Volume 24, Part 2 (New York, P. F. Collier and Son, 1909-1914), Part II, Section 1. Accessed January 5, 2020 at https://www.bartleby.com/24/2/201.html.

[2] Immanuel Kant, Critique of Judgment (New York: Hafner, 1968), 100-101.

[3] Augustine, Exposition of the Psalms 24:2, quoted in Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture, Old Testament VII, Psalms 1-50, edited by Craig A. Blaising and Carmen S. Hardin, Thomas C. Oden, general editor (Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity, 2008), 185

[4] Denis Dutton, The Art Instinct: Beauty, Pleasure, and Human Evolution (New York: Bloomsbury, 2009), 14–15.

[5] “Ridley Scott and Matt Damon on Going to Jordan to Recreate Mars.” Yahoo! Entertainment (September 29, 2015). https://www.yahoo.com/entertainment/ridley-scott-and-matt-damon-on-going-to-jordan-to-230136329.html.

[6] See Richard Lewontin, “Billions and Billions of Demons,” a review of Carl Sagan, The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark, New York Review of Books (January 9, 1997). This quote was discovered by Philip Johnson and given widespread attention in his book, Defeating Darwinism by Opening Minds (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1997), 81.