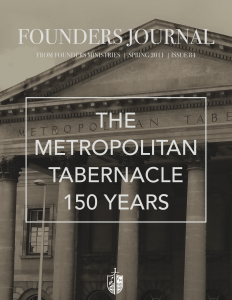

When the newly constructed Metropolitan Tabernacle opened in 1861 it was baptized with a series of services involving every relevant sphere of interest in the progress of Spurgeon’s ministry. Henry Vincent called the impressive building, “the noblest temple ever raised by Non-conformist zeal” [MTP, 1861, 331]. The two week long inaugural services showed it to be the concretion of the noblest vision for gospel proclamation ever conceived in the mind of one non-conformist minister. These services climaxed with a celebration of the exuberant grace of God toward sinners though a series of messages on the distinguishing doctrines of sovereign, effectual, irresistible grace. The denouement ensued with a proclamation that none of the elect shall be absent in the final census, that the whole world, therefore, is the field of legitimate labor for God-called, Spirit-gifted gospel teachers, and that an assurance of one’s standing before God in salvation is not only possible and a great privilege of grace, but the duty of all to seek and not to rest content until it is attained.

A prayer meeting convened at 7 AM March 18, 1861 attended by 1000 people. Spurgeon and several others prayed and a hymn was sung that narrated “that joyous gospel which we trust will long be proclaimed within our hallowed walls.” The song of a present salvation founded upon an eternal covenant sung on this day would echo through the walls at Newington for the next thirty-one years of Spurgeon’s ministry–and beyond.

Saved from the damning power of sin,

The law’s tremendous curse,

We’ll now the sacred song begin

Where God began with us.We’ll sing the vast unmeasured grace

Which, from the days of old,

Did all his chosen sons embrace,

As sheep within his fold.The basis of eternal love

Shall mercy’s frame sustain;

Earth, hell, or sin, the same to move,

Shall all conspire in vain.Sing, O ye sinners bought with blood,

Hail the Great Three in One;

Tell how secure the cov’nant stood

Ere time its race begun.Ne’er had ye felt the guilt of sin

Nor sweets of pard’ning love,

Unless your worthless names had been

Enroll’d to life above.O what a sweet exalted song

Shall rend the vaulted skies,

Then, shouting grace, the blood-wash’d throng

Shall see the Top Stone rise.

One week later, another prayer meeting was held. That afternoon, March 25, Spurgeon preached the first sermon in the newly constructed Tabernacle. Spurgeon set forth an uncompromising Christocentric purpose in his preaching ministry at the Tabernacle. He pronounced the now famous words, “My venerable predecessor, Dr. Gill, has left a body of divinity, admirable and excellent in its way; but the body of divinity to which I would pin and bind myself forever, God helping me, is not his system of divinity or any other human treatise, but Christ Jesus, who is the sum and substance of the gospel; who is in himself all theology, the incarnation of every precious truth, the all-glorious personal embodiment of the way, the truth, and the life” [MTP, 1861, 169]. One that preaches Christ must preach His full deity, His full humanity, that He is the only mediator between God and man, that He is the only lawgiver for the church, that He is the only king of the church. This Christ must be preached doctrinally, experimentally and practically. He must be preached comprehensively–not just five strings, well-plucked till virtually worn out–but all the strings, the entire doctrine of Christ in all His beauty. This theme alone can reconcile the affections of the very diverse commitments that have existed among the great men of the various denominations. The theme of Christ unites them, though they might never have found fellowship in life, their unity since death has been founded solely on their common love for and trust in a perfect Savior [MTP, 1861,172-76].

The Monday evening service consisting of an “Evangelical Congratulation” delivered by W. Brock seconded Spurgeon’s emphasis on the preaching of Christ, propounded the renovating power of the gospel to fallen humanity, defended the holy tendency of preaching the doctrines of grace, and commended a full evangelical ministry brimming with intellectual and doctrinal integrity. “It is a vile and wicked calumny,” Brock said with a peculiarly spurgeonic emphasis, “that our doctrines of grace lead to licentiousness.” “Never was there anything more palpably contrary to the truth.” Interspersed were comments about the particular impact that the ministry in the tabernacle would have. “We know that the place will be the birthplace of precious souls through successive generations; we know that the place will be like a great big human heart, throbbing, pulsating with beneficence and benevolence, obtained directly from the cross of Christ; and this great big human heart will be propelling far and near a thousand of influences, which shall be for ‘glory to God in the highest, for peace on earth, and good will towards men’” [MTP, 1861, 183]. About Spurgeon personally, Brock said, “My brother will not stand here as the statesman stands in the senate house, or the advocate at the bar, or the lecturer on the platform of an Athenaeum.” He would “as well accoutered and well furnished as they are mentally, intellectually” but chiefly his eloquence would consist of his might in the Scriptures. He would be a fellow worker with God whose expectations would not be merely natural but preter-natural as a demonstration of the Spirit and of power. “With all that may be persuasive or argumentative or pathetic, with all that may be properly and intentionally adapted to commend the truth to every man’s conscience in the sight of God, there will be the energy whereby God is able to subdue all things unto himself” [MTP, 1861, 181].

At a special meeting of contributors on Tuesday evening, March 26, speakers gave many words of admiration for the structure and its capacious magnificence. Such grandeur of space seemed particularly appropriate for Spurgeon who could not be limited to a small number or a small space. Rejoicing in that increased exposure this new setting would give to the doctrines so faithfully preached by Spurgeon–election, effectual calling, justification by the righteousness of Christ, all centering on the atoning sacrifice of Christ–one speaker said that it was no use trying to confine the eagle to a little cage for either he would break his wings or break the cage. He rejoiced that “it was not the wings of the eagle which had been broken, but the cage.” Now the noble bird would have sufficient room to career through the firmament. Spurgeon’s immutable resistance to debt went on full display as he reiterated a vow never to enter the facility until debt free. Needing now only £4200 for completion, including several superficial internal amenities, a collection of something more than £3700 had been collected allowing the congregation to enter and complete the installation of carpet and some fittings as money became available. Upon this announcement the congregation rose to sing the doxology “with enthusiasm at the request of the rejoicing pastor” [MTP, 1861, 190]. More important than this debt-free status, however, in Spurgeon’s desires was an increase in prayer for his faithfulness in ministry. Interspersed with exclamations of confidence in God, Spurgeon laid his requests for prayer before the congregation of contributors. “What am I to do with such a work as this upon me? It is not the getting-up of this building; it is not the launching of the vessel–it is keeping her afloat.” How could he as a young man, a feeble child, go in and out among such a people. “More than I have done to advance His Gospel, I cannot promise to do, for God knoweth I have preached beyond my strength, and worked and toiled as much as one frame could do; but I hope that in answer to your prayers I may become more prayerful, more faithful, and have more power to wrestle with God for man, and more energy to wrestle with man for God.” He felt compelled to call upon all those that had benefitted spiritually from his ministry to pray for him.

If you have been edified, encouraged, or comforted through me, I beseech you carry me before God. And especially you that are my spiritual sons and daughters, begotten of me by the power of the Holy Ghost, you who have been reclaimed from sin, you who were wanderers in the wild waste until Jesus met with you in the Music Hall, in Exeter Hall, or in Park Street–you, above all–you must pray for me. Oh, God, we pray Thee, let multitudes of the vilest of the vile here be saved. I had rather die this night, on this spot, and end my career, than lose your prayers. My aged members, deacons, and elders, will not you be more earnest than ever? My younger brethren, my co-equals in age, comrades in battle; ye, young men, who are strong to overcome the wicked one, stand up with me, shoulder to shoulder, and give me your help [MTP, 1861, 192].

Mr. Moore, a churchman, spoke last in the meeting indicating that he had followed and marveled at Spurgeon even in the earlier days when he was not considered so sane as he was now. Had the responsibility of raising such a building debt free fallen on the shoulders of a Churchman, the process would have dragged on for ten years. Spurgeon, he believed, had done “the Church of England more good than any clergyman in it” and that neither St. Paul’s, nor Westminster Abbey, nor the theaters would be open for Sunday preaching without his influence.

The next evening, Wednesday March 27, representatives of the neighboring churches came together. More than 4000 people from these churches assembled for this meeting chaired by Dr. Edward Steane. Steane had been active for years as a secretary in the Evangelical Alliance. In 1852 he edited a volume entitled The Religious Condition of Christendom [London: James Nisbet and Co., 1852]. He viewed Romanism and Infidelity as the two great enemies of evangelical Christianity and would obviously be pleased that such a Hercules of evangelical truth, so fearless in confronting destructive error, was now situated with such abundant opportunity for influence in the city of London. He surveyed the structure with a sense of awe, wonder, and gratitude–“the largest sanctuary which had ever been reared by such churches as theirs to the service and glory of God” [MTP, 1861, 193]. Steane further indicated his pleasure by noting that “providence might have brought a brother who would have been an element of strife and discord, but God’s grace had brought a brother among them, with whom they were one in feeling, one in doctrine, one in heart, one in sympathy, and one in Christ.” When Spurgeon responded to the celebrative introductory remarks of Steane that included a standing expression of love from both ministers and laity of the surrounding churches, he marked his experience as filled with grace and hope that such kindness had been his consistent experience from these neighbors. Spurgeon felt that it “was not easy for people to love him” since he often preached some “very strong things.” The strength of his language, however, conformed to the needs of a shallow and careless age, and, by divine blessing, he found greater love and esteem from a variety of friends than if he attempted to speak smoothly. Spurgeon hoped for quarterly meetings of the various ministers that they might pray together and encourage each other in ministry to the glory of Christ. William Howieson offered Spurgeon “Godspeed” and multiplied blessings though, as the closest neighbor to the new Metropolitan Tabernacle he stood to lose the most members. He hoped that every pastor would now “horse the old coach better” to meet the new competition [MTP, 1861, 194]. Howieson believed that the presence of Spurgeon in the Tabernacle would make all of his neighbors better preachers. Steane added that such an impetus to improvement, not only intellectually and functionally, but spiritually, would serve the cause of the kingdom well. His tenure of forty years as a pastor taught him something of the unique challenges faced by a gospel preacher.

He knew they were in danger of neglecting their own hearts, whilst they were professedly taking care of the souls of others; that they were tempted to substitute a critical study of the Scriptures as ministers for a devout and daily perusal of them as Christians; that they were apt to perform or discharge the duties of their office in a professional sort of way, instead of feeling themselves the power of those truths which they declare to others; that they were in danger of resting satisfied with a fervour and elevation of soul in public, instead of a calm and holy communion with God in private. If they were to give way to those things, then as the result of diminished spirituality, there would be a barren ministry [MTP, 1861, 195].

As more ministers in the surrounding area contemplated what it meant that Spurgeon, now outfitted with a facility of massive proportions, would have on their congregations, they emphasized their joint interest in the gospel success of all congregations. They had not come to place altar against altar but to publish the same God, the same gospel, the same Christ, the same atonement as an open fountain for the cleansing from sin. Punctuating these tributes were notices of Spurgeon’s unusual natural gifts and acquired skills as well as the profound aptness of such a structure as the Tabernacle for his use. Spurgeon had a “powerful and eloquent voice, and was well able to arouse the indifferent, and to make those who were careless and unconcerned thoughtful with regard to their souls” [MTP, 1861, 196]. The free-will gifts that purchased the Tabernacle came from those that recognized the “spiritual gifts with which God had endowed their friend, and were desirous that a building should be reared capable of holding as many thousands as could be conveniently reached by his diapason voice” [MTP, 1861, 198]. Newman Hall, pastor at Surrey Tabernacle, indicated the impressiveness of Spurgeon and the new setting, as a rhetorical device in pointing beyond both to the preeminence of Christ.

It is not the splendour of architecture, nor your glorious portico and majestic columns; not this graceful roof and these airy galleries, and these commodious seats so admirably arranged for worship and for hearing; it is not the towering dome, or the tapering spire emulating the skies; It is not clustering columns and intersecting arches through which a dim religious light may wander; it is not all these–though I do not despise the beauties of architecture–which is the glory of the church . It is not the splendor of the pulpit–the eloquence that can wave its magic wand over a delighted audience till every eye glistens and every heart beats with emotion–the erudition that from varied stores of learning can cull its illustrations to adorn the theme–the novelty of thought, and sentence, and argument that can captivate the intellect and satisfy the reason–the fancy that can interweave with the discourse the fascinations of poetry and the beauties of style; no, it is not any one of these, nor all of these together. But it is Christ in his real and glorious divinity; Christ in his true and proper humanity; Christ in the all and sole sufficiency of his atonement; Christ in His in-dwelling spirit and all prevailing intercession. This is the glory; and without this, though we had all other things, Ichabod must be written on the walls of any church [MTP, 1861, 200].

On Good Friday, March 29, Spurgeon preached on Romans 3:25 on Christ Set Forth as a Propitiation to what he referred to as an “immense assembly” [MTP, 1861 206]. On that evening he preached again out of Song of Solomon, “My beloved is mine, and I am his.” Entitled The Interest of Christ and His People in Each Other, the sermon emphasized how Christ had made the church His own (“I am my Beloved’s”) and the embedded reality that such a claim makes the Beloved One ours (“And He is mine”). As he worked out the implications of this joint interest of Christ and His people, Spurgeon applied it to the opening opportunity for missionary labors in China. “Now, I do honestly avow,” he stated in a moment of surprising revelation, “if this place had not been built, and I had had nothing beyond the narrow bounds of the place in which I have lately preached, I should have felt in my conscience bound to go to learn the language and preach the Word there.” In God’s providence, however, it had been built and he knew that “I must here abide, for this is my place.” Almost a month later these same thoughts he would publish in a sermon on the Great Commission. Now, as later, he pointed out that others would not have such a gracious tie to keep them from answering to such an opportunity to show that indeed they do belong to Christ. A full persuasion of that reality would “make life cheap, and blood like water and heroism a common thing, and daring but an every-day duty, and self-sacrifice the very spirit of the Christian life” [ MTP, 1861, 214].

On Easter Sunday evening, March 31, on the first Sunday that the Tabernacle held the Sabbath service, Spurgeon preached from 2 Chronicles 5 and 7 on the dedication of the Temple during the reign of Solomon. The elaborately appointed Temple, constructed at immense expense, received the presence of God in the cloud and in the fire, that same presence that accompanied the people in the wilderness wanderings. Had that evidence of the divine presence not invaded and filled the temple, the entire ceremony and effort would have been in vain. So it must be with the Metropolitan Tabernacle. When the glory fell the people fell to praise and said, “For his mercy endureth forever.” “This is a grand old Calvinistic Psalm,” Spurgeon commented and proceeded to drive the point home.

What Arminian can sing that? Well, he will sing it, I dare say; but if he be a thoroughgoing Arminian he really cannot enjoy it and believe it. You can fall from grace, can you? Then how does his mercy endure forever? Christ bought with his blood some that will be lost in hell, did he? Then how did his mercy endure for ever? There be some who resist the offers of Divine grace, and after all that the Spirit of God can do for them, yet disappoint the Spirit and defeat God! How then does his mercy endure forever? No, no, this is no hymn for you, this is the Calvinists’ hymn [MTP, 1861, 219].

On Tuesday, April 2, the London Baptist Brethren gathered for a celebration of this achievement, which, rightly so, they viewed as a significant accomplishment for the whole denomination. Spurgeon saw this meeting as an opportunity to promote “our success as a united body.” The church belonged to “all the Baptist denomination,” not to any one man or one church in particular, but first to God and next “to those who hold the pure primitive ancient Apostolic faith” [MTP, 1861 225]. Spurgeon allied himself to the historic Baptist principle of liberty of conscience as well as the view of Baptist origins that saw Baptists, not as descending from Rome, but as existing in an independent and constant stream of witness in an “unbroken line up to the apostles themselves.” Baptists were “persecuted alike by Romanists and Protestants of almost every sect” while Baptists had never been persecutors. They had never, nor do they now, “held it to be right to put the consciences of others under the control of man.” Though willing to suffer, they desired no assistance from the state and consistently refused to “prostitute the purity of the Bride of Christ to any alliance with government, and we will never make the Church, although the Queen, the despot over the consciences of men” [MTP, 1861, 225]. Sir Morton Peto, member of the House of Commons and a Baptist, chaired the meeting. He joined Spurgeon in celebrating the commitment that Baptists had fervently maintained to liberty of conscience and viewed the erection of the Tabernacle as a splendid monument to the voluntary principle–that Christ’s people would love Him and seek the proclamation of His name without the forceful exaction of monetary aid from an unwilling people.

J. Howard Hinton spoke and, as others had done in other services, pointed to some of the unique gifts of Spurgeon. “Long may the life be spared which is so devotedly and laboriously spent; the intellectual powers which acquire and supply so large an amount of Evangelical truth; and the magnificent voice which, with so much facility, pours it into the ear of listening thousands” [MTP, 1861, 227]. His theme brought attention to the necessity of the work of the Spirit, “wherein lies the entire success of the Evangelical ministry.” Present day conversion indicated that only small measures of the Spirit were being given but a time would come in accordance with God’s sovereign pleasure and power when the “whole world may be rapidly subdued to God” [MTP, 1861, 228]. Alfred Thomas spoke about the necessity of maintaining the integrity of the Baptist ordinances; a Mr. Dickerson spoke of the differences that existed from the time of Benjamin Keach to the time of the building of the Metropolitan Tabernacle; Jabez Burns reminded those gathered that the Baptist principle of personal responsibility had built not only the Tabernacle but provided the compulsion for a free church in a free society. Burns also reminded that the Baptist commitment had been tested when Roger Williams founded Rhode Island “where he gave the utmost freedom of conscience, and did not demand from any of those who chose to dwell with him the least infringement of their Christian liberties” [MTP, 1861, 234]. Spurgeon commended a bill of Peto concerning the burial of unbaptized persons, encouraged the brethren to support efforts to provide good literature for preachers, and proposed an aggressive church-planting initiative among the Baptists. Baptists should not cower in shame before any Englishman for they possessed the poetry of Milton, the allegory of Bunyan, and the pastoral ministry of Robert Hall. He noted the distinctions that existed even among the group gathered as a show of strength. “Here am I a strict Baptist, and open communion in principle; some of our brethren are strict in communion, and strict in discipline; some are neither strict in discipline nor in communion. I think I am nearest right of any, but you all think the same of yourselves, and may God defend the right [MTP, 1861 231-32].

On April 3 representatives of the various denominations met for the purpose of celebrating Christian unity. The speakers kept to the subject of unity in diversity. The spirit of the meeting was established when the chairman, Edward Ball of Cambridgeshire, emphasized his desire that all Christians adopt the great maxim “that in essential they should have unity; in non-essentials, liberty; and in everything they ought to have charity” [MTP, 1861, 235]. They should have “large eyes for each other’s excellencies, and small vision for each other’s defects.” When praying and praising and distributing the Bible they put aside the points of division and labored together for the pre-eminence of Christ and His Word.

W. G. Lewis of Bayswater was bold enough to announce that he could have no unity with a man that did not hold to the inspiration of God’s sacred Word. Nor did he find sufficient ground for unity with one that denied the “utter degeneracy of the entire human race in consequence of sin.” The same held true for the necessity of deep conviction of sin in order to salvation, the atonement of Christ, the deity of Christ and the doctrine of the Trinity. While liberty in non-essentials should be observed, one must not forget that true unity cannot exist merely in such freedom as a passive requirement, but must actively embrace those truths that are considered essential [MTP, 1861, 241-42]. He need have no fear that his statement of essentials as foundational to real unity would be offensive to Spurgeon or dissonant to the future melody of Spurgeon’s long song.

Octavius Winslow took the pulpit on the evening of April 4 and preached “Christ’s Finished Work” based on the words of Jesus recorded in John 19:30: “It is Finished.” Before the year was out, on December 1, Spurgeon himself would take this text for a sermon. Winslow echoed Spurgeon’s emphasis on the cross and forecast what Spurgeon’s message would be for the next thirty years when he proclaimed that the secret of the might of one that would contend earnestly for the truth lay in the “simple, bold, uncompromising presentation of the Atoning and finished Sacrifice of Christ–the up-lifting, in its naked simplicity and solitary, unapproachable grandeur, of the Cross of the Incarnate God, the instrument of the sinner’s salvation, the foundation of the believer’s hope, the symbol of pardon, reconciliation, and hope to the soul; in a word, the grand weapon by which error shall bow to truth, and sin give place to righteousness; and the kingdoms of this world long in rebellion against God, crushed and enthralled, shall yield to Messiah’s scepter, spring from the dust, burst their bonds, and exult in the undisputed supremacy and benign reign of Jesus” [MTP, 1861 243]. Christ’s cry was the cry of a sufferer, the language of a savior, and the shout of a conqueror. Nothing may be placed beside the completed work of Christ as an aid or supplement in His role of suffering and conquering Savior. Adding to the accumulating hopes and admonitions concerning the future occupation of the Tabernacle, Winslow concluded, “And now from my heart I ask the blessing of the triune God upon my beloved brother, the grand substance of whose ministry I believe from my very soul is to exalt the finished work of Jesus. And I pray that this noble edifice, reared in the name and consecrated to the glory of the triune God, may for many years echo and re-echo with his voice of melody and of power in expounding to you the glorious doctrines and precepts of Christ’s one finished atonement” [MTP, 1861, 248].

After services on Sunday, April 7, the congregation gathered on Monday evening to have their time of inaugurating their new place of worship. Spurgeon’s father, John Spurgeon, served as chairman and conveyed regrets from his own father for not being there. The joy of the occasion might indeed be his death, and he wanted to die in his own church. James Smith reveled in the theological heritage of the church and its perennial usefulness in the conversion of sinners. His prayer while he was pastor that God would “cram the place” had been fulfilled under Spurgeon; the blood-stained banner of the cross was continually unfurled in the preaching and the baptismal waters did not rest. Spurgeon himself spoke about peculiarities of the church in its maintenance of an eldership as a separate office from the deacons, thus avoiding an unbiblical amalgamation found in many churches. This arrangement had made him “the happiest man on earth, and when he had any troubles, it was very seldom they came from the Church.” In addition, he maintained a strict policy about baptism and church membership, opposite to many of the churches of the Baptist Union, but an open policy toward communion. This was just as it should be he believed–strict discipline and unlimited fellowship with all the church of God [MTP, 1861, 261]. He illustrated both the strictness and the openness on the next two evenings. Stowell Brown preached a sermon on Christian baptism on Tuesday. On Wednesday, Spurgeon exemplified the “unlimited fellowship” by presiding with ministers of other churches in celebrating the Lord’s Supper at the Tabernacle with believers from “all denominations” [MTP, 1861, 264]. As Spurgeon continued his analysis of the peculiarities of his congregation, he pointed to their advocacy of a specific confession of faith, as any lively church should. When life appears so does definite belief. “Creedless men were like dead limbs and would have to be cut off.” In his congregation, Spurgeon proposed that it would be difficult for anyone to confute even the youngest member of the church “on any of the five points.” They all loved the doctrines of grace. Even with such a strong policy doctrinally, he had been accused by some of preaching Arminian sermons. Should it appear that way to some, he did not bother to correct the impression–Calvinism, Arminianism, Fullerism, or Mongrelism–none of the names were material to him in comparison with clarity, candor, and faithfulness in proclamation of the Bible. The Word of God defied all restricted systems and one day would appear thoroughly consistent and be displayed in beautiful harmony, although presently the narrow constriction of the human mind might not be able to discern it. In addition to these happy conditions of the church, Spurgeon pointed to three strengths: Prayerfulness consistently bolstered all the work. Young converts were zealous for truth and action. Great unity characterized all that they did as a congregation. The danger, of which all were aware, was “that they might grow proud and be lifted up.” Some, he indicated, were very anxious about him on that point, but he knew that divine grace, not advice from conceited individuals, would cure the evil.

William Olney represented the deacons in giving a detailed catalogue of things for which to be thankful. Prominent among these blessings stood the “goodness of God in sparing to them the life of their beloved pastor, who had been engaged in very arduous and incessant labour for the last seven years, and yet was among them then in every respect a better and happier man for all his labour in the Master’s cause” [MTP, 1861, 261]. The blessings he noted had prepared them for the reception of more and gave particular importance to the text “Unto whomsoever much is given, of him shall be much required” [MTP, 1861 262]. Another of the former pastors, Joseph Angus, followed Olney with another load of advice, though “Mr. Spurgeon had told them they were overdone with advice.” He would follow the deacon rather than the pastor on this occasion and continue with admonitions in light of the massive blessings and the golden future of opportunities. Spurgeon was doing a work that none of his predecessors from Gill on forward had been permitted to do. They should maintain their commitment to the old doctrines and a large-hearted catholic spirit. Such was the soundness of their creed and the scripturalness of their doctrines. “They held firmly to the views of John Calvin; they held the spirituality of the Christian church, and saw clearly into the meaning of the ordinances.” This they should continue and “be always ready to give their hand and heart to all who loved the Lord Jesus Christ in sincerity and in truth” [MTP, 1861, 262]. Spurgeon then presented framed testimonials to two deacons that had been members of the church for more than fifty years and deacons for twenty-five and twenty-two years respectively, James Low and Thomas Olney.

In his sermon on Christian Baptism, Stowell Brown showed the prominence of believers’ baptism in the Scripture and in early church history. He indicated that every attempt to support infant baptism biblically was remote and weakly inferential and employed a group of biblical references that had far more compelling applications and interpretations than their employment in defense of infant baptism. He acknowledged that their view of baptism made Baptists distinct from a large groups of other denominations but that hardly justified the charge that Baptists made too much of baptism. He countered, “When we say of this ordinance that it regenerates the soul,–when we say that herein persons are made ‘members of Christ, children of God, and heirs of the kingdom of heaven,’–when we rush with all haste to baptize the sick and the dying, and when we refuse to accord to those who die unbaptized, the rites, the decencies, the charities of Christian burial,–then tell us, for indeed we shall deserve to be told, that we do most monstrously exaggerate the importance of this ordinance.” Obedience to God and avoiding error justified the Baptist separation from Christian brethren on the grounds of differences on baptism. “A thing may not be essential, and yet it may be very far from unimportant.” Baptists regard infant baptism as the “main root of the superstitious and destructive dogma of baptismal regeneration,” a doctrines they oppose as Protestants, “the chief corner-stone of State Churchism,” a status they oppose as Dissenters and as “unscriptural,” and “to everything that is unscriptural we, as disciples of Jesus Christ, must be opposed.” No matter how widely others may differ from Baptists, he hoped they would admit that “we are only doing what is right in maintaining what we believe to be the truth of God with reference to this matter” [MTP, 1861, 272].

Visible testimony to Spurgeon’s recitation of the church’s commitment to a confessional stance on the doctrines of grace came on the afternoon of April 11. Sermons on the five doctrines as represented by the acronym TULIP were preached. Before those messages. Spurgeon gave an impassioned defense of the system as a whole. Calvinists did not differ in essentials with evangelical Arminians such as Primitive Methodists and Wesleyans. Between Protestant and Papist, between Christian and Socinian essential differences existed that altered the very substance of the faith. Calvinists and Methodists, though disagreeing in the formal construction of their doctrine on certain issues, often expressed themselves on issues of prayer and salvation experience with harmonious sentiments. Spurgeon pointed to Wesleyan hymns that embodied Calvinist truth. Spurgeon found election, final perseverance, and effectual calling set forth in strong terms. Against Calvinism straw men abounded; and Spurgeon was not short of answers to these false representations. Addressing objections concerning the damnation of infants, fatalism, sovereign and unmerited reprobation, failure to preach the gospel to the unregenerate, and enmity to revivals, Spurgeon cleared away false allegations. He made it clear that hyper-Calvinism would not drive him away from true Calvinism. He spoke of it as he found it in Calvin’s Institutes and in his expositions. “I have read them carefully,” he informed his listeners. And his system was taken from the source and not from the common repute of Calvinism. Nor did he necessarily care for the name, Calvinism, but for the “glorious system which teaches that salvation is of grace from first to last.” Spurgeon noted, for his own part, he found that preaching these doctrines had not lulled his church to sleep, “but ever while they have loved to maintain these truths, they have agonized for the souls of men, and the 1600 or more whom I have myself baptized, upon profession of their faith, are living testimonies that these old truths in modern times have not lost their power to promote a revival of religion” [MTP, 1861, 303].

Calvinism also has strengths of “little comparative importance” that nevertheless, “ought not to be ignored.” The system was “exceedingly simple” and thus easily accessible by unlettered minds. At the same it “excites thought” and has been a challenge to the most active and far-reaching minds in intellectual history. Calvinism is “coherent in all its parts,” and fits so well together that the more pressure that is applied “the more strenuously do they adhere.” Spurgeon asserted that “You cannot receive one of these doctrines without believing all.” Consent to any of these doctrines in its true form made the others follow of necessity. Though, as stated above, one might listen to his preaching on some occasions and think that he preached Arminianism, he did not accept the idea that any doctrinal contradictions existed in Scripture, and when considered in their most unadulterated form every point in the doctrines of grace arose from the biblical logic of human sin and salvation by pure grace. His emphasis on this was insistent.

Some by putting the strain upon their judgments may manage to hold two or three points and not the rest, but sound logic I take it requires a man to hold the whole or reject the whole; the doctrines stand like soldiers in a square, presenting on every side a line of defence which it is hazardous to stack, but easy to maintain. And mark you, in these times when error is so rife and neology strives to be so rampant, it is no little thing to put into the hands of a young man a weapon which can slay his foe, which he can easily learn to handle, which he may grasp tenaciously, wield readily, and carry without fatigue; a weapon, I may add, which no rust can corrode and no blows can break, trenchant, and well-annealed, a true Jerusalem blade of a temper fit for deeds of renown [MTP, 1861, 304].

More important than these reasons, Spurgeon saw the doctrines as purely biblical and thoroughly consistent with Christian experience. These doctrines created neither sloth nor coldness nor corrupt lives, but zeal for truth and holiness. After John Bloomfield preached on “Election” and Evan Probert preached on human depravity, the meeting adjourned until half past six.

Spurgeon again took the floor to introduce the final three speakers and briefly introduced the sessions with another defense of the Calvinistic scheme of salvation. It is easy to raise objections against the system, Spurgeon conceded, as it easy to raise objections against virtually anything, even one’s own existence. But objections against Calvinism were not a tithe of the difficulties that might be pointed out in the opposite scheme. They do not unfold every aspect of the depth of divine wisdom or exhaust the fountains of God’s purpose, but they do serve as a safe and consistent biblical guide that shall find every wave a friend to speed our ship on its journey toward the fullness of the divine glory. J. A Spurgeon preached on Particular Redemption, James Smith on Effectual Calling and William O’Neill on Final Perseverance of Believers. Prior to the final presentation by O’Neill, Spurgeon had a further comment to make on the purpose of the day’s messages. He had observed that some seemed not to have sufficient patience to listen to a doctrine fully brought out. They wanted illustrations, anecdotes and metaphors. John Newton spoke of these doctrines like lumps of sugar that could not well be given undiluted to the people but must be diffused throughout all the sermons. This day, however, was purposefully given over to the exposition of these doctrines in undiluted form that the overall impact of their truth might be felt at once. That fact called for one final apology for the emphasis of the day.

Has it never struck you that the scheme of doctrine which is called Calvinistic has much to say concerning God? It commences and ends with the Divine One. The angel of that system stands like Uriel in the sun; it dwells with God; he begins, he carries on, he perfects; it is for his glory and for his honour. Father, Son, and Spirit co-working, the whole Gospel scheme is carried out. Perhaps there may be this defect in our theology; we may perhaps too much forget man. I think that is a very small fault, compared with the fault of the opposite system, which begins with man, and all but ends with him. Man is a creature; how ought God to deal with him? That is the question some theologians seem to answer. The way we put it is–God is the Creator, he has a right to do as he will; he is Sovereign, there is no law above him, he has a right to make and to unmake, and when man hath sinned, he has a right to save or to destroy. If he can save, and yet not impair his justice, heaven shall ring with songs; if he destroy, and yet his goodness be not marred, then hell itself with its deep bass of misery, shall swell the mighty rollings of his glorious praise. We hold that God should be most prominent in all our teaching; and we hold this to be a guage [sic] by which to test the soundness of ministers. If they exalt God and sink the sinner to the very dust it is all well; but if they lower the prerogatives of Deity, if he be less sovereign, less just, less loving than the Scripture reveals him to be, and if man be puffed up with that fond notion that he is anything better than an unclean thing, then such theology is utterly unsound. Salvation is of the Lord, and let the Lord alone be glorified [MTP, 1861, 322].

On the Sunday subsequent to these Thursday expositions, Spurgeon preached a message that summarized the emphases of the day. In “The Last Census” based on Psalm 87:6 “The Lord shall count, when he writeth up the people, that this man was born there” Spurgeon focused on what is written, whose names will not be there, whose names will be there, who will do the writing, and for what purpose is the writing done. He emphasized the individuality of the judgment, that fatal power of final impenitence, the certainty of salvation for all that flee to Christ, the perfect equity of God in determining the contents of the writing, and the truths demonstrated and mysteries solved when the writing is done. All God’s jewels, all His sheep, and the names in the Lamb’s book of life will be written. Satan will discover that he has gained not even one of them. Satan finally was overcome even in Job on the dunghill, David on the rooftop, and Peter in Pilate’s Hall. The great Shepherd of the sheep preserved them in gentle proddings or startling reprimands but always in harmony with a subdued and humbly compliant will. The decree of God and the acts of man will be seen as in perfect consonance.

[A]nd how strange shall it seem as that great sealed book is now unclasped, it is found that all who were written there have come, nay come as they were written, come at the hour ordained, come in the place predestinated, come by the means foreknown, come as God would have them come, and thus free agency did not defeat predestination, and man’s will did not thwart the eternal will. God is glorified and man free. Man–the man as he proudly calls himself–has obeyed God as truly as though he knew what was in God’s book, and had studied to make the decree of God the very rule and method of his life. Glorious shall it be when thus that book shall prove the mystic energy which went out from between the folded leaves–the mysterious Spirit that emanated from the eternal throne–that unseen, unmanifested, sometimes unrecognized mysterious power, which bowed the will and led it in silken chains, which opened up the understanding and led it from darkness into light, and melted the heart and moved the Spirit, and won the entire man to the obedience of the truth as it was in Jesus [MTP, 1861, 280].

Having inundated the first weeks of Tabernacle meetings with strong affirmations of Calvinistic truth, “with shouts of sovereign grace” [MTP, 1861, 280], always with the evangelistic emphases that he felt were embraced within the system, Spurgeon followed on April 21 with a sermon on the Great Commission entitled “The Missionaries’ Charge and Charta.” Spurgeon admitted that he had seriously considered if it were his duty to leave England where so many churches and ministers existed to go to a land of pioneer labors. “I solemnly feel that my position in England will not permit my leaving the sphere in which I now am, or else tomorrow I would offer myself as a missionary.” He indicated that one burden of his prayers was that many from that church would go as missionaries, a prayer fulfilled exponentially. In relating that prayer he again said, “I have questioned my own conscience, and I do not think I could be in the path of duty if I should go abroad to preach the Word, leaving this field of labour; but I think many of my brethren now labouring at home might with the greatest advantage surrender their charges, and leave a land where they would scarce be missed, to go where their presence would be as valuable as the presence of a thousand such as they are here” [MTP, 1861, 287]. In closing the message he made a similar statement as he called for others to feel a fire that could not be quenched to go where others had not gone. “Brethren, I envy any one among you–I say again with truth, I envy you–if it shall be your lot to go to China, the country so lately opened to us. I would gladly change places with you. I would renounce the partial ease of a settlement in this country, and renounce the responsibilities of so large a congregation as this with pleasure, if I might have your honours” [MTP, 1861, 281, 288].

Between these bookends of missionary desire, Spurgeon loaded a missionary theology. He showed that Jesus’ command to teach all nations was a generous and gracious manifestation of love and divine condescension. The simple and singular method of teaching brought together the nature and needs of men with the message and prerogatives of God. As children we need to be dealt with gently and patiently and as ignorant and rebellious we need to have our lies replaced with truth and our recalcitrance replaced with child-like submission. If they will not be taught, they will not enter the Kingdom of Heaven. In spite of all obstacles–ignorance and sophistication, barbarity and passivity, degradation and culture, literate and illiterate–teach them.

The fact has been proved, brethren, that there are no nations incapable of being taught, nay, that there are no nations incapable afterwards of teaching others. The Negro slave has perished under the lash, rather than dishonour his Master. The Esquimaux has climbed his barren steeps, and borne his toil, while he has recollected the burden which Jesus bore. The Hindoo has patiently submitted to the loss of all things, because he loved Christ better than all. Feeble Malagasay women have been prepared to suffer and to die, and have taken joyfully suffering for Christ’s sake. There has been heroism in every land for Christ; men of every colour and of every race have died for him; upon his altar has been found the blood of all kindreds that be upon the face of the earth. Oh! Tell me not they cannot be taught. Sirs, they can be taught to die for Christ; and this is more than some of you have learned. They can rehearse the very highest lesson of the Christian religion–that self-sacrifice which knows not itself but gives up all for him [MTP, 1861, 283-84].

Emphasizing the unique position of Baptists in fulfilling this commission purely and in the order given because of their enduring ecclesiological conviction that teaching always should precede baptism, he told his hearers “we ought to be first and foremost, and if we be not, shame shall cover us for our unfaithfulness.” He held up the call insistently before his congregation, “I hear that voice ringing in the Baptist’s ear, above that of any other, ‘Go ye, therefore, and teach all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost’” [MTP, 1861, 284]. Christ’s commission mirrored the history of the church in its reflection of Christ’s suffering. The church never could “plough a wave without a spray of gore.” The church must suffer to reign, must die to live, must be stained in red to be clothed in purple, and must be buried and forgotten in order to be delivered of the man-child. It was by death that Christ became the mediator possessed of all power for the redemption of His people [MTP, 1861, 285]. Thus, the church has a right to all places; no place can take from it its right to teach. “Do ye pass decrees forbidding the gospel to be preached? We laugh at you!” Gospel heralds have rights without limits. They may not be forbidden by any earthly power to omit obedience to the risen Lord for His authority extends to all places throughout all times. The heralds of peace and salvation may not set their foot on any place to which Christ does not have the right. Resolutions against such are mockeries and waste-paper. “The church never was yet vassal to the state, or servile slave to principalities and powers, and she neither can nor will be” [MTP, 1861, 285-86]. For Christ not only has right, but He has might. He has might to change the hearts of princes and rule by providence to open nations through revolution or through increase of technology. In addition He has might in heaven. Cherubim and seraphim bow before Him, He may grant the plentitude of the Spirit and clothe His ministers with power, and He has unrestrained warrant to intercede with the Father.

At the time of this message, 1600 church members heard him while the entire congregation was 6000. He plead with them all, member and listener alike, to consider the implications of there being none in such a congregation willing to go.

Jesus! Is there not one? Must heathens perish? Must the gods of the heathen hold their thrones? Must thy kingdom fail? Are there none to own thee, none to maintain thy righteous cause? If there be none, let us weep, each one of us, because such a calamity has fallen on us. But if there be any who are willing to give all for Christ, let us who are compelled to stay at home do our best to help them. Let us see to it that they lack nothing; for we cannot send them out without purse of scrip. Let us fill the purse of the men whose hearts God has filled, and take care of them temporally, leaving it for God to preserve them spiritually [MTP, 1861, 288].

Spurgeon was determined that the Metropolitan Tabernacle would be home to a joyful, clear, and full presentation of the Doctrines of Grace. From there, the neighborhood, the city, the country, the kingdom and the world should hear the same message–the successful execution of an eternal purpose proposed by the Father to honor the Son with a people gained by dent of His own grace and perfect conformity to the wisdom, justice, and holy love of the Father. The opening of the Tabernacle served to announce that message as the foundation for all that would be done and preached there and culminated with an impassioned proclamation of the certain success of the divine undertaking with a fervent plea for God’s people to be the means of its world-wide advance.