Confessions can be an aid to understanding the Bible. They developed from the desire of Christian teachers to help Christians give clear testimony to biblical truth. At the most fundamental level, confessions are succinct lessons exploring the Bible. How is this so?

First, confessions are founded on a long history of biblical exposition. Seeking to give the true meaning of a text and discerning its fitness with other texts has been the manner of dealing with Scripture since it first began to be committed to writing (Deuteronomy 31:9-13). The text was to be read, meditated on, taken to heart, and interpreted according to its true meaning (Joshua 1:8; 2 Kings 22:8-13; Nehemiah 8:1-8). Jesus did this to the disciples that walked the Emmaus road with him (Luke 24:25-27). The obligation of truthful exposition of Scripture was one of the major tasks of the apostles that served as a foundation for their revelatory expansion of the full body of revealed truth (1 Peter 1:10-12). As Paul gave exposition to the doctrine of justification by faith in defense of the revelation given to him, he consistently did it in terms of its relation to Old Testament Scripture (Galatians 3:7-9; 10-14, 22; 4:21-31). He pointed to Christ as the one perfectly to be the fulfillment of it all (5:3-6; 6:14-16).

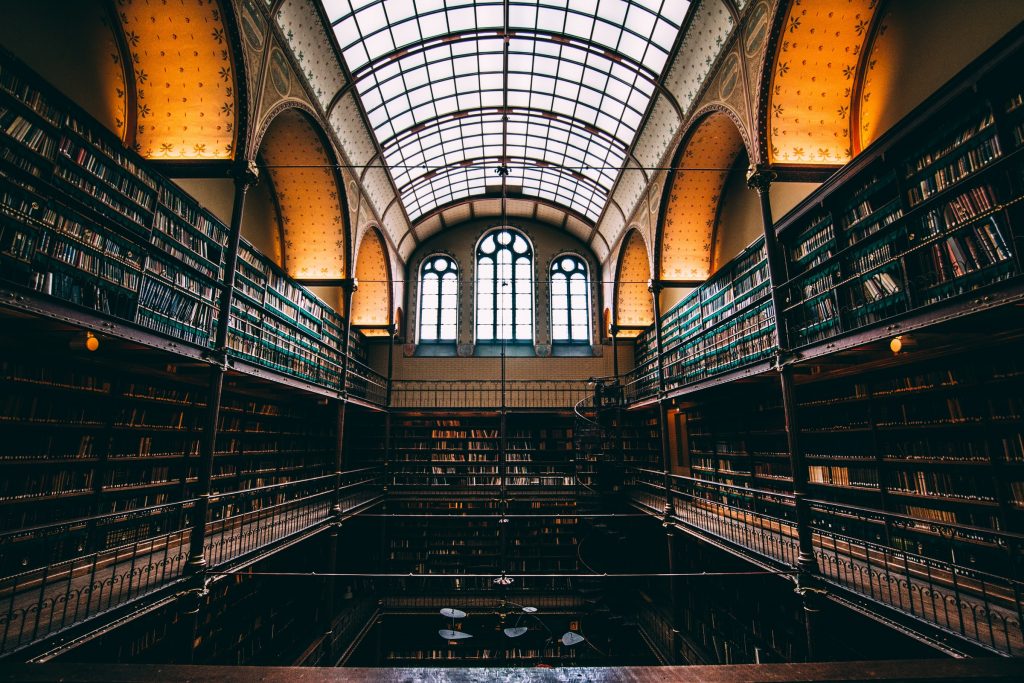

Christian teachers have been interacting with the Scripture to discern its meaning and establish its truth since the immediate post-apostolic age to the present. Pivotal passages concerning creation, providence, the fall of humanity from innocence into sin, the nature of God, the Trinity, the mystery of the person of Christ, the purpose of the death of Christ, and the character of the eternal state have been cited, massaged, clarified, and given the position of a proof text for understanding particular points of biblical revelation. A confession of faith is a testimony to the integrity of this process, its mistakes and its corrections, and the manner in which the clarity of Scripture is established.

Second, confessions provide a synthesis of this exposition. Early confessions of faith such as the Apostles’ Creed give testimony to a trinitarian arrangement of the pivotal issues of Christian truth. The Creed of Nicea (325) gives an unmistakable affirmation of the deity of Jesus Christ excluding all viewpoints that stopped short of affirming the divine essence of Jesus. The Constantinopolitan creed (381) reaffirmed this and added a robust affirmation of the personhood, full deity, and distinct activities of the Holy Spirit. The Symbol of Chalcedon (451) returned to the issue of Christ and gave a succinct synthesis of the biblical and theological discussion of decades. It affirmed the complexity of Christ’s person as consisting of a fully divine nature (the eternal Son of God), a full human nature received of his mother Mary, and both existing without confusion, without change, and without division or separation in one single person, the Lord Jesus Christ.

Among the most important of the Reformation syntheses of exposition was the doctrine of imputed righteousness as essential to the doctrine of justification. The Second London Confession states the idea in these words: “not for anything wrought in them, or done by them, but for Christ’s sake alone, not by imputing faith it self, the act of believing, or any other evangelical obedience to them, as their righteousness; but by imputing Christ’s active obedience unto the whole law, and passive obedience in his death, for their whole and sole righteousness, they receiving, and resting on him, and his righteousness, by faith.” The New Hampshire Confession employs the same concept with greater economy of language: “Justification consists in the pardon of sin and the promise of eternal life, on principles of righteousness; that it is bestowed not in consideration of any works of righteousness which we have done, but solely through his own redemption and righteousness, by virtue of which faith his perfect righteousness is freely imputed to us of God.” These words reflect considerable attention to biblical exposition and polemical engagement with opposing viewpoints by Roman Catholics.

Third, confessions provide connections between the doctrines of Scripture. We find the story of the Bible distilled in redemptive-historical fashion in the arrangement of a confession. Included, one finds chapters on the necessity of divine revelation, the existence and attributes of God, Trinity, creation, providence, fall, redemption in its constituent parts, final judgments, and the eternal state. Not only do we discover, therefore, a synthesis of biblical exposition in individual doctrines but a synthesis of the whole Bible. This synthesis engages God’s eternal purpose as effected in the linear historical development set forth in Scripture. For example, nine consecutive chapters of the Second London Confession treat the experience of salvation under these topics in consecutive order: “Of effectual calling, . . .Of justification, . . . Of adoption, . . . Of sanctification, . . . Of saving faith, . . . Of repentance unto life and salvation, . . . of good works, . . . Of perseverance of the saints, . . . Of the assurance of grace and salvation.” These show how the whole experience of salvation, undivided in the eternal intent of God expressed in the covenant of redemption, can be discerned in its separate parts. Such a division synthesized into an orderly arrangement can be a great aid in the proclamation of discerning and probing sermons for the sake of a healthy examination of Christian faith.

The New Hampshire Confession provides an example of how certain articles of a confession summarize and synthesize and highlight the importance of a clear grasp of other doctrinal articles. Article 17 states, “We believe that there is a radical and essential difference between the righteous and the wicked; that such only as through faith are justified in the name of the Lord Jesus, and sanctified by the Spirit of our God, are truly righteous in his esteem; while all such as continue in impenitence and unbelief are in his sight wicked, and under the curse; and this distinction holds among men both in and after death.”