Second London Confession

Chapter II

Of God and of the Holy Trinity

The chapter entitled, “Of God and of the Holy Trinity,” like the first article on Scripture, establishes foundational truths to support the confessional superstructure that follows. The order is important. Chapter one stated, “Although the light of nature, and the works of creation and providence do so far manifest the goodness, wisdom, and power of God, as to leave men inexcusable; yet they are not sufficient to give that knowledge of God and His will which is necessary unto salvation.” Such a situation makes “the Holy Scriptures to be most necessary.” First, therefore, a revelatory authority is needed, shown by a variety of evidences to be authentic, and then a view of God Himself, derived from revelation, is needed. These two fundamental realities, Scripture and God, serve as touchstones by which to judge the chapters that follow in the confession. Do they align with the authority of Scripture? Do they manifest the consistency of the perfections attributed to God with the actions subsequently ascribed to him? Is God sufficient for the number, order, and nature of the decrees, their outworkings, and their consummation as developed in Scripture? Are such decrees and all their attendant parts worthy of the God that is described in this article?

The chapter has three robust paragraphs. The first affirms those absolute attributes of God as he is in himself and gives a brief introduction as to how those attributes function in relation to an order outside of himself. These two ways of looking at the divine attributes are called absolute and relative. The second paragraph, contextually combining the absolute attributes with their relative manifestations, affirms God’s sovereignty over and independence of any creature. The third paragraph affirms the Trinitarian reality of this single deity—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—undivided in essence yet eternally related to each other by an eternal mode of being and “several peculiar relative properties.” Peculiar does not mean strange or odd, but having properties incommunicable to the other persons, each person having distinctive traits exclusively his own.

Each paragraph of this chapter will be quoted in full from the Second London Confession. Numbers denoting Scripture proofs are omitted. In italics are words that were added by its composers and not found in the Westminster Confession of Faith. Words of that confession omitted from the Second London are put in brackets.

Paragraph One

The Lord our God [There] is but one only living and true God; whose subsistence is in and of Himself, infinite in being and perfection; whose essence cannot be comprehended by any but Himself; a most pure spirit, invisible, without body, parts, or passions, who only hath immortality, dwelling in the light which no man can approach unto; who is immutable, immense, eternal, incomprehensible, almighty, every way infinite, most holy, most wise, most free, most absolute; working all things according to the counsel of His own immutable and most righteous will, for His own glory; most loving, gracious, merciful, long-suffering, abundant in goodness and truth, forgiving iniquity, transgression, and sin; the rewarder of them that diligently seek Him, and withal most just and terrible in His judgments, hating all sin, and who will by no means clear the guilty.

God in the Absolute

That which should be evident to all from the very nature of being also is revealed as thoroughly consistent with the purest and most absolute conceptions of which the human mind is capable—there is only one “living, and true God.” To conceive of two gods—infinite, supreme in being, having no other being equal to him but having all things dependent on him—is impossible. The very perception of God rules out rivals. So Scripture asserts: “Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God, the Lord is one” (Deuteronomy 6:4). As Judah considered its unfaithfulness to God, it posed this question, “Have we not all one Father? Has not one God created us?” (Malachi 2:10). In Isaiah 40-44 God challenges all other so-called gods to match him in qualifications for goodness and summarizes the contest with the confidence of triumph: “Thus says the Lord, the King of Israel and his Redeemer, the Lord of hosts: I am the first and I am the last; besides me there is no god. Who is like me? Let him proclaim it” (44:6, 7). Jeremiah also proclaims, “But the Lord is the true God: he is the living God and the everlasting king” (Jeremiah 10:10).

God’s “subsistence is in and of himself.” This phrase is not in the Westminster Confession of Faith [WCF], but was added by the Particular Baptists to give an immediate emphasis to the idea of self-existence. From no other being or place does he derive his essence. He revealed himself to Moses with a name that affirmed his immutable self-existence, “I am who I am” (Exodus 3:14). Every particular way in which his infinite perfection is manifest is natural to him, an eternal essential property operating in its pristine originality: “Whom did he consult, and who made him understand? Who taught him the path of justice, and taught him knowledge, and showed him the way of understanding?” (Isaiah 40:14). The paradigm behind all aspects of intelligence, purpose, understanding, knowledge, moral reflex, convictions of right and wrong are in God and he has distributed them to certain of his creatures in varying degrees to lead us to find in him the perfection of all things. None has given any of these things to him; they originate with him and he distributes to others according to his own will. Paul told the Athenians, “The God who made the world and everything in it, being Lord of heaven and earth” is not “served by human hands as though he needed anything, since he himself gives to all mankind life and breath and everything … that they should seek God, in the hope that they might feel their way toward him and find him” (Acts 17:24, 25, 27). Had God acquired anything from another place than his own perfect being, then such would be original and, therefore, before and better than he, which contradicts the idea of deity and the explicit testimony of Scripture.

It is impossible to conceive of absolutely nothing; granted this as impossible to contradict, there must be one being independent of all others in all ways. All dependent and mutable things must be explained by the existence of one independent and immutable thing. Such a being must of necessity be infinite for it is impossible to conceive of anything existing outside of and apart from this being. If this being is the first, then he is of necessity infinite for there can be no place for existence apart from and outside of his necessarily perfect and immense existence. All other things that exist have the reason for their being and the mode of their being in this original, self-subsisting, infinite, unpartitioned being. “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth (Genesis 1:1). … It is he who made the earth by his power, who established the world by his wisdom, and by his understanding stretched out the heavens. (Jeremiah 10:12). … All things were made through him, and without him was not anything made that was made (John 1:3) … Who has put wisdom in the inward parts or given understanding to the mind? (Job 38:36) You hem me in, behind and before, … where shall I flee from your presence? (Psalm 139:5, 7) … In him all things hold together (Colossians 1:17). . and he upholds the universe by the word of his power (Hebrews 1:3).” All material existence comes from the power of God and continues its existence from moment to moment by that same power; all indications of design and purpose come from his wisdom and understanding; every level of intelligence from the lowest to the highest is a revelation of the Being through whom they were given existence. He has received nothing from them, but they everything from him. His “subsistence is in and of himself, infinite in being, and perfection.”

The phrase, “whose essence cannot be comprehended by any but himself,” again, does not appear in the WCF but was added. When the word “incomprehensible” appears in the WCF, it is in the midst of a list of positive, absolute attributes; the framers of the 2LC wanted to note that incomprehensibility is not an absolute, but a relative, attribute. God is incomprehensible to the creature but not to himself. This insertion shows the great difficulty of speaking about God strictly in the absolute. From the word “cannot” one naturally infers the presence of the finite in its inability to achieve exhaustive definition of God. Cannot is not part of the vocabulary for considering God in the absolute, for in the absolute, God indeed is comprehended in that he knows and loves himself perfectly and the specter of an incomplete knowledge has no shadow of existence.

He to himself in his perfect three-personed fellowship, unhindered by any insufficient knowledge or apprehension of himself, has no shadows in his comprehension of his infinitely glorious simplicity and singularity of his essence. Nor is this compromised in any degree or way by his knowledge of the distinctive properties eternally exhibited in the three persons. “No one knows the Son except the Father, and no one knows the Father except the Son . . . No one comprehends the thoughts of God except the Spirit of God” (Matthew 11:27; 1 Corinthians 2:11; italics added). Scripture itself informs us of God’s incomprehensibility by giving comparisons as to the limitations necessarily involved in our finiteness. Finiteness finds further complications in the darkness that has descended on the mind because of sin. “Although they knew God, they did not honor him as God or give thanks to him, but they became futile in their thinking, and their foolish hearts were darkened” (Romans 1:21).

God’s ultimate incomprehensibility to us, however, does not mean that we are unable to make any true statements about God as far as they go. His merciful condescension to reveal himself would be utterly vain if the creatures had no capacities of mind, affection, and spirit that corresponded to the categories within which God’s revelation comes. Though we cannot know him exhaustively, we can know accurately whatever he chooses to reveal.

All statements, whether of graces, commands, or attributes, about God, whether of Father, Son, or Holy Spirit that are not specifying some trait or operation distinctive of the respective person may be taken as a revealed attribute of or duty toward God. For example, when Paul closes Ephesians with the words, “Grace be with all who love our Lord Jesus Christ with love incorruptible” (Ephesians 6:24), he does not mean that only Christ is worthy of such love. Surely the command to love God applies to Father, Son, and Spirit and that command finds a particular kind of expression in one’s love to Christ. When Paul observed concerning the Thessalonians, “You turned to God from idols to serve the living and true God, and to wait for his Son from heaven, whom he raised from the dead, Jesus who delivers us from the wrath to come,” he used the term God specifically for the Father, calling him the “living and true God.” This does not mean that the Father alone is the “living and true God” but that his work of raising Jesus from the dead points to him, as opposed to the idols they formerly worshipped, as a God (no article in Greek) living and true, not a god of wood or stone or metal. All of those statements made of God, or the Lord, as simply considered (e.g. In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth; Are you not from everlasting, O Lord my God, my Holy One?; For thus says the Lord to the house of Israel: Seek me and live.” Genesis 1:1; Malachi 1:12; Amos 5:4) are revelations of that which is essentially one in God.

The confession accordingly gives an impressive list of traits that God has revealed concerning himself, employing an extended phrase that piles up attributes—not without comparison to the restrictions of finiteness—showing why God’s existence is impossible to comprehend by any created thing– “A most pure spirit, invisible, without body, parts, or passions, who only hath immortality, dwelling in the light, which no man can approach unto, who is immutable, immense, eternal, incomprehensible, Almighty, every way infinite, most holy, most wise, most free, most absolute.” Such a barrage of verbal concepts distilled from Scripture focuses on the reality that God is not confined to any spatial limitations but is an illimitable presence of perfect beauty, holiness, intelligence, and power. The framers of the 2LC added the words “who only hath immortality, dwelling in the light, which no man can approach unto.” They also added the phrase, “every way infinite”

All of him in all of his power and holiness is everywhere. Nothing exists outside of, or away from, him. All things created, in him have their being. As an invisible, immense, unbodied, unpartitioned spirit there is no single point anywhere in all of existence disconnected from the Triune God in all his power, perfect knowledge, invincible purpose, and glorious holiness. He is “the King of ages, immortal, invisible, the only God” (1 Timothy 1:17). Not only does his immensity (his essence being absolutely undivided) affirm the character of his omnipresence, it affirms that his power is upholding all other things in their own existence and in their relation to all other things—“He upholds the universe by the word of his power” (Hebrews 1:3). Although other rational beings are immortal by divine decree and by the necessity of the eternal implications of their moral responsibility, only God intrinsically is immortal—“In him was life and the life was the light of men; who alone has immortality” (John 1:4; 1 Timothy 6:16).

The attribution that he is without passions means that his affections are perfect, expressive always of the infinite joy and love eternally resident within himself. He is an overflowing, exuberant, irrepressible fountain of perfectly symmetrical, exactly integrated, attributes constituting absolute goodness (Exodus 33:19). All of those relations and actions within himself and those outside himself manifest this unchanging goodness. His infinite holiness and wisdom means that every interaction he has with the created order is expressive of his unchangeable moral perfection and wise disposal of all things according to his decrees and for his glory. He is not acted upon by the created order with the result that he alters his plans, his affections, or senses any disturbance from other powers or agents. That he is “most absolute” means that nothing about him can possibly change for he cannot increase in any perfection—he cannot gain any knowledge, acquire more wisdom, develop a new skill, enhance a virtue, or complete his plans. All is present and perfect with him. His counsel will stand and he will accomplish all his purpose (Isaiah 46:10)

God in Relation

Such observations lead one naturally to reflect on God in his relation to a finite order. Since he himself is “most absolute,” and all his perfections are known intrinsically and intuitively within himself, the sphere in which his perfections may be revealed and, therefore, observed as they unfold in layer upon layer of disclosure, is the finite order he brings into being outside himself. The created order, particularly that part that makes moral choices, experiences his unchanging goodness as a spectrum of affections exhibited as just responses to actions or merciful interventions according to his purposes of grace. This order exists, as the confession continues, so that his capacity of “working all things according to the councel of his own immutable, and most righteous will, for his own glory” will have eternal occupation in showing and sharing with other beings his glory. Some experience God’s purpose in their lives as “most loving, gracious, merciful, long-suffering, abundant in goodness and truth, forgiving iniquity, transgression and sin.” Those who experience God’s goodness as a display of mercy “shall sing of the ways of the Lord, for great is the glory of the Lord” (Psalm 138:5). They will be trained by such mercy to say confidently, “The Lord will fulfill his purpose for me,” and say to the Lord with gratitude, “Your steadfast love, O Lord, endures forever.” (Psalm 138:8).

Saul of Tarsus, who became Paul the Apostle, saw the sovereign purpose of God unfold for him. Having lived from the time of his birth, through early training and zealous application of talent and entrenched conviction, as an enemy of Christ and his followers, the time came in God’s counsel to call the persecuting zealot “by his grace” and to reveal his Son to and in him. Paul knew that he had been set apart before he was born and had been singled out to preach Christ “among the Gentiles” (Galatians 1:13-16). His actions deserved the displeasure of God and an intense display of eternal wrath, but as the “foremost” of sinners, God purposed to display in an overflowing manner “his perfect patience as an example to those who were to believe in him for eternal life” (1 Timothy 1:13-16).

On the other hand, divine goodness also operates discreetly as wrath in many cases. In such cases, God is “most just, and terrible in his judgments, hating all sin, and who will by no means clear the guilty.” Though flowing from an unchanging purpose and immutable virtue, we observe this as a just response to human transgression. Though settled before time, it appears existentially as God’s immediate engagement with the choice of the creature. For example, as pure wisdom, he speaks to simpletons and fools, “Because I have called and you refused to listen, have stretched out my hand and no one has heeded, because you have ignored all my counsel and would have none of my reproof, I also will laugh at your calamity; I will mock when terror strikes you” (Proverbs 1:24-26). In the same way, Scripture presents what is ultimately a fruit of grace as a divine response to those who desire to find rest before God: “You keep him perfect peace whose mind is stayed on you, because he trusts in you” (Isaiah 26:3).

Not only from the necessary implications of all ideas of immutability and perfection, but from a broad synthesis of relevant passages of Scripture, we are confident that God does not change or develop courses of action in this world as a response to the decisions of any of his creatures. His purposes are eternal, original propensities of his nature. He administers them outside of himself in the created order through virtually infinite displays of variegated demonstrations of power, intelligence, beauty, discernment, counsel, graces, and acts of holy justice.

All human actions are responses to a nexus of factors interwoven in cause and effect relationships. All of them are determined by one or a combination of several ways of perceiving what lies before us. Some are immediate perceptions of physical reality or emotional impact while others involve a line of rational reflection through which we select one option as more desirable than another. All of them, however, exist within the framework of the original cause and the final cause of God. Originating from the “riches and wisdom and knowledge of God,” that is “from him,” proceeding in light of his unsearchable judgments and inscrutable ways, that is, “through him,” and culminating in the manifestation of and praise of his “glory forever,” that is, “to him,” (Romans 11:33, 36) within this time-space continuum, God embedded his own responses to the moral actions of humanity. We must affirm both that “the gifts and calling of God are irrevocable” and that the Gentiles “received mercy because of their [Israel’s] disobedience.”

God has established both the existence and the principles of operation of all material, non-moral things and sustains their being and interactive operations—“He brings out their host by number, calling them by name, by the greatness of his might, and because he is strong in power not one is missing” (Isaiah 40:26). His control of nature, however, is in the interests of his moral purposes. “Was your wrath against the rivers, O Lord? Was your anger against the rivers, or your indignation against the sea, when you rode on our horses, on your chariot of salvation?” (Habakkuk 3:8). Every part of God’s creation eventually serves a moral purpose—that of manifesting as fully as possible within a finite realm the infinite goodness, majesty, wisdom, and glory of God, particularly as arranged for the salvation of his people.

While such immediate determination is more easily embraced in the natural, material, non-moral order of the world, tracing the paths of such immutable decrees operative in the moral realm may be illustrated in several instances. “As for you, you meant it for evil against me, but God meant it for good to bring it about that many people should be kept alive, as they are today” (Genesis 50:29); “This Jesus, delivered up according to the definite plan and foreknowledge of God, you crucified and killed by the hands of lawless men” (Acts 2:23); “They have stumbled over the stumbling stone, as it is written, ‘Behold, I am laying in Zion a stone of stumbling, and a rock of offense;” (Romans 9:32, 33); “Therefore God sends them a strong delusion, so that they may believe what is false, in order that all may be condemned who did not believe the truth but had pleasure in unrighteousness” (2 Thessalonians 2:11, 12; “They will make her [the prostitute] desolate and naked, and devour her flesh and burn her up with fire, for God has placed it into their hearts to carry out his purpose by being of one mind and handing over their royal power to the beast, until the words of God are fulfilled” (Revelation 17:16, 17). Actions that are terrible crimes in those who do them are arranged by God within the fabric of motivations and impulses of fallen and rebellious creatures to bring about his predestined end.

The difficulty that appears from such decrees arises from the reality that human decisions, as well as angelic actions, bear eternal moral consequences for their eternal states of existence. This reality of moral decisions within a context of moral determination, however, reflects the way that God himself issues all his decrees and operates in every event of this world. His nature determines the structure of moral categories and the nature of moral responsibility. His truthfulness always draws praise, not in spite of an intrinsic immutable disposition to speak truthfully, but, because of such a disposition. He is earnestly sought after as good even though his moral actions are determined by the holy perfection and absolute righteousness of his nature. “My soul yearns for you in the night; my spirit within me earnestly seeks you. For when your judgments are in the earth, the inhabitants of the world learn righteousness” (Isaiah 26:9). He works “all things according to the councel of his own immutable, and most righteous will, for his own glory.”

Paragraph Two

God, having all life, glory, goodness, blessedness, in and of Himself, is alone in and unto Himself all-sufficient, not standing in need of any creature which He hath made, nor deriving any glory from them, but only manifesting His own glory in, by, unto, and upon them; He is the alone fountain of all being, of whom, through whom, and to whom are all things, and He hath most sovereign dominion over all creatures, to do by them, for them, or upon them, whatsoever Himself pleases; in His sight all things are open and manifest, His knowledge is infinite, infallible, and independent upon the creature, so as nothing is to Him contingent or uncertain; He is most holy in all His counsels, in all His works, and in all His commands; to Him is due from angels and men, [and every other creature,]whatsoever worship, service, or obedience, as creatures they owe unto the Creator, and whatever He is further pleased to require of them.

Having discussed divine attributes from both an absolute and a relative perspective, this paragraph takes closer notice of the relation of God to the creation. Though God has created with a purpose that arises from his own immutable will, this does not indicate any dependence that he has on the creature. The present paragraph delineates the manner in which God, as the one who is “unto himself all sufficient,” positions himself vis-a-vis the order he has brought into being outside of himself. Given the truth that God’s perfection means that neither in his nature nor in his opera ad intra and opera ad extra are there any superfluities, how does one discuss creation without implying that God is dependent on it in any sense? This paragraph establishes five points about the relation of the Creator to the creature.

One, God is declared to be self-sufficient “in and of Himself.” Nothing is lacking in his self-existent state of life, glory, goodness, and blessedness. No creature, therefore, can add anything to him nor can he derive from them any glory. His relation to the creature is one of manifesting “His own glory in, by, unto, and upon them.” The beauty of the world adds nothing to the beauty of God. Rather, all the beauty that it has he has bestowed on it. The creation tantalizes us with the unspeakable glory of the uncreated original beauty that has created by his own word such varieties beauty. He imposes on it form, symmetry, color, sound, purpose, and interdependence all around us. The mysterious harmony and interlacing pockets of purpose, large and small, add nothing to the perfect teleology resident within the mind of God but inform us that our task of discovering the relationships of order established by God will never come to a satisfactory end. “Can you bind the chains of the Pleiades or loose the cords of Orion? Can you lead forth the Mazzaroth in their season, or can you guide the Bear with its children? Do you know the ordinances of the heavens? Can you establish their rule on earth” (Job 38:31-33). No, none can do this, for God alone has established these things. We can only look at it and seek to search it out with wonder, all the time realizing that as inscrutable as these principles of arrangements in creation are, God is above them, his glory transcends them and is manifest “in, by, unto, and upon them.”

Two, as the “alone fountain of all being,” he acts upon all his creatures in accordance with the purpose for which he created them. No creature exists except in accord with the creating power and sustaining energy of God. They do not come into being by an extraneous power or for any purpose undetermined by God. “He hath most sovereign dominion over all creatures, to do by them, for them, or upon them, whatsoever Himself pleaseth.” Nebuchadnezzar had to be taught that “the Most High rules the kingdom of men and gives it to whom he will.” In the process of having that lesson forcefully impressed on him, Nebuchadnezzar also confessed “all his works are right and his ways are just; and those who walk in pride he is able to humble” (Daniel 4:25, 37).

Three, the reason that “in his sight all things are open and manifest” is not so much related to his present ability to observe all things thoroughly and simultaneously (though he has that), but because his “knowledge is … independent upon the creature.” His knowledge does not come subsequent to the existence of the creature so that his knowledge of it depends on the creature, but precedes its existence and is present eternally in his own purpose before the ages were brought into being.

As the Psalmist considers the perfection of God’s knowledge of him and the impossibility of being out of his presence he said, “In your book were written, every one of them, the days that were formed for me, when as yet there were none of them” (Psalm 139:16). The Bible does not allow us to consider for a moment that the world stands on its own power as an independent center of being. It exists by the power of God, according to the will of God and for the glory of God. The functioning of the bird’s wing, the fish’s fin, the firefly’s tail, the leaf’s system of exchanging gases, the beaver’s teeth, the eagle’s eye, and the speed of light, finite but virtually incomprehensible to us, were spoken into existence by God. The human body was crafted and the human spirit and mental operations vitally expressive of the brain’s intricate inner operations arose from a peculiarly expressive self-interest of God (Genesis 1:26-28; 2:7, 21-25).

He knows all these things, not through present observation and study, but because they originated in his power and infinite rationality. They reflect his infinite intelligence, wisdom and purpose distributed in finite portions in innumerable displays of wonderful and awesome beauty and complementary existence. “I praise you for I am fearfully and wonderfully made. Wonderful are your works; my soul knows it very well” (Psalm 139:14). His works of creation do not add any knowledge to him but are expressions of his power and godhead (Romans 1:19, 20).

This is true not only of their raw existence but of the time of their existence and all the interactions of their existence until they fade and pass away to be replaced by others. God says, “I form light and create darkness, I make well-being and create calamity, I am the Lord, who does all these things” (Isaiah 45:7). Truly the confession gives a clear and sound affirmation when it says, “Nothing to him is contingent or uncertain.”

Four, the operations of the entire creation are to show the holiness of God. “He is most holy in all His counsels, in all His works, and in all His commands.” The world does not operate as a mere amoral mechanism with God remaining aloof. As Nebuchadnezzar learned in confrontation with the Lord zealous for his own glory, “all his works are right and his ways are just; and those who walk in pride he is able to humble” (Daniel 4:37). Jesus used the winds and the waves to strike fear into the hearts of the disciples on at least two occasions. In both of these he demonstrated the tininess of their faith as well as the insufficiency of their physical strength and endurance to deal with the natural forces that he himself made and that he could control by any means he chose. Whether by voice or by apparent suspension of the “laws” of nature he showed he was over these things, was not limited in any sense by their apparent independence, and used them to prompt and reveal spiritual realities in his people (Matthew 8:23-27; Mark 6:45-52; John 2:1-11; See also virtually the entire book of Job).

Five, the appropriate position of the creature before the Creator is one of worship. The WCF states, “To him is due from angels and men, and every other creature, whatsoever worship, service, or obedience he is pleased to require of them.” The 2LC both omits from and adds to this statement. “To Him is due from angels and men, [omitting ‘and every other creature’ perhaps as superfluous, since as far as we know there are no other rational creatures that can render worship], whatsoever worship, service or obedience, as creatures they owe unto the Creator [italicized phrase added to show that worship results not only from command but from the very nature of the Creator-creature distinction], and whatever He is further [added] pleased to require of them.”

Certain circumstances of worship under both the Old and New Covenants further define how worship is to be executed. By natural consequence of the creature/Creator distinction the fact of the obligation of worship is established, but by revelation the manner of its practice is established. Violations of these revealed ways of worship are taken with utmost seriousness by God (Numbers 2:15; 1 Chronicles 13:9, 10; 15:2, 15; Hebrews 8:3-5). The New Testament has several loci of instruction concerning the content and manner of worship, but it is freed from the typological and ceremonial details that defined the worship of Israel (John 4:19-24; 1 Corinthians 12:12-30; Ephesians 5:19-21; Colossians 3:16, 17; 1 Timothy 2; 2 Timothy 4:1-5; Hebrews 8:1-7; 9:1-10; 10:19-25; 13:7-17).

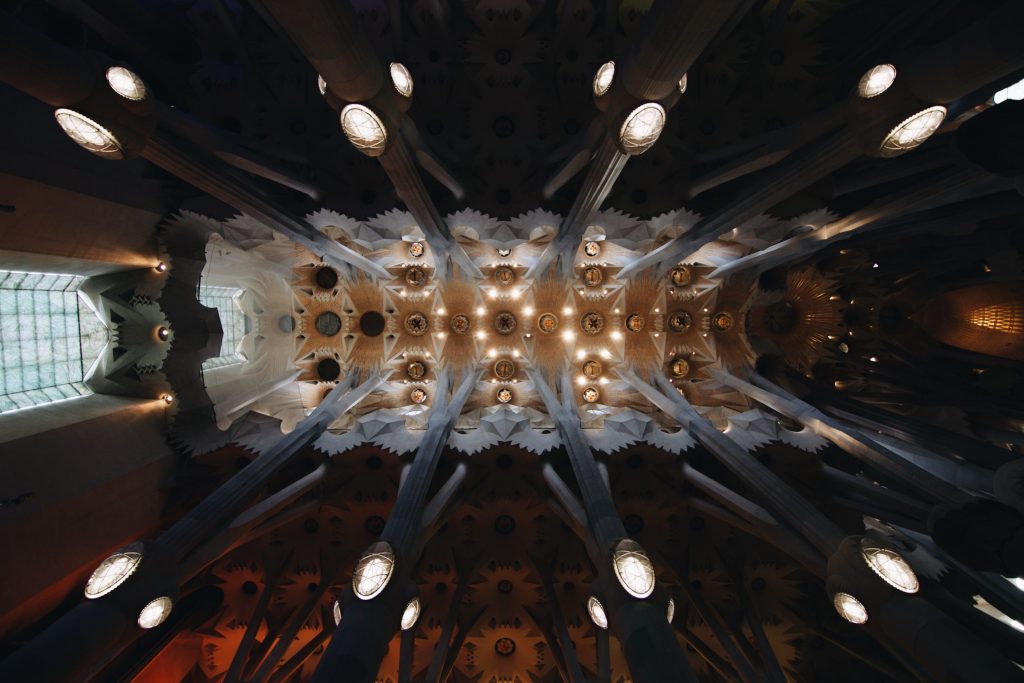

One of the most vital aspects of worship as revealed in Scripture is that we worship a God eternally consisting of three persons, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. This reality constitutes the singular glory of the Christian revelation and consequently of Christian worship. Also it calls for the most reverent and cautious use of language in theological discussion.

Paragraph 3

In this divine and infinite Being [In the unity of the Godhead] there are three subsistences [persons], [God] the Father, [God] the Word [Son] (or Son), and [God the] Holy Spirit [Ghost], of one substance, power, and eternity, each having the whole divine essence, yet the essence undivided: the Father is of none, neither begotten nor proceeding; the Son is eternally begotten of the Father; the Holy Spirit [Ghost eternally] proceeding from the Father and the Son; all infinite, without beginning, therefore but one God, who is not to be divided in nature and being, but distinguished by several peculiar relative properties and personal relations; which doctrine of the Trinity is the foundation of all our communion with God, and comfortable dependence on Him.

Basic Trinitarianism a Matter of Pure Revelation

The doctrine of a triune God—striking and challenging, but intriguing and provocative—is a matter of pure revelation. Sam Waldron noted, “Paragraph 3 is interesting because it combines statements from the First London Baptist Confession, the Westminster Confession and the Savoy Declaration. It thus provides a more detailed statement of the Trinity than any of them.”1 A. A. Hodge wrote, “These propositions embrace the Christian doctrine of the Trinity (three in unity), which is not part of natural religion, though most clearly revealed in the inspired Scriptures.”2 Robert Shaw wrote, “The doctrine of the Trinity is not discoverable by the light of nature, or by unassisted reason. It can only be known by divine revelation, and it is amply confirmed by the Holy Scriptures.”3 John Brown wrote: “It is fully evident, that there are precisely THREE persons in the one godhead, or divine essence or substance.” After these words Brown gives 32 instances from Scripture that state clearly the existence of three persons in this one singular undivided essence, a true “mystery” that can be sustained only by divine revelation. He surmises from his evidence,

In which multitude of inspired texts we find one person under the name of Jehovah, God, Father, or represented as primary agent; a second under the name of the Word, Son, Servant, Angel, Anointed, Jesus Christ, Desire of all nations, and represented as the Saviour of men; and a third, called the Spirit, Holy Ghost, God, Lord, &c.4

J. P. Boyce does not arrive at his discussion of the Trinity until chapter 14 of the Abstract of Systematic Theology. Ten of those chapters discussed the attributes of God. As he entered the discussion of “Personal Relations in Trinity,” he stated, “The nature of these relations can be indicated in no other forms than those set forth in Scripture. They are matters of pure revelation.” Further, he argued that “the fact of their existence is beyond the attainment of reason” and cannot be “strengthened by philosophical speculations.”5

If a biblical expositor/theologian arrives, therefore, at a conclusion, on the basis of exegesis, that the Bible teaches there is only one God who is infinite, eternal, and unchangeable in his being, wisdom, power, holiness, justice, goodness, and truth, and who alone is self-existent having created all things and presently sustaining all things that are not him, we would conclude that such an exegete, in all of those assertions, has arrived at a notable body of biblical truths about God.

If he further concludes through a synthesis of biblical texts, using the analogy of faith, that this God exists eternally in three persons without division of essence or disruption of divine simplicity with each person fully participating in and manifesting the infinite excellence of essential deity in perfect unison with each other person, we would conclude that such an exegete is biblically sound and in full accord with the historic witness of the church.

Further, if this person arrives at the conclusion that the persons of the Triune God are denominated as, and exist in eternal relation as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit with identifiable aspects of distinct personhood operating immanently and internally that give immutable standing to this tri-fold denomination within this one God, we would embrace such syntheses as truthful and biblical. This biblically engendered view of God, as far as it goes, presses us forward in a desire to understand yet more truths to be affirmed about this God that we commonly worship and adore.

Many realities about this God we do not comprehend—some because none of us grasps all of the biblical revelation with perfect clarity, some because they are as yet unrevealed, and an overwhelming “some” because God is fully comprehensible by none but himself. Other doctrinal propositions, however, may, in the thinking of some, have sufficient biblical data to be clearly supported beliefs. Other biblical thinkers do not find the synthesis of the data sufficiently coherent to establish a doctrine. Unless demonstrable heresy is involved, these points constitute areas in which constructive and fraternal dialogue can occur without bringing recrimination on our discussion partners. We should feel free, however, to make our cases as strongly as possible, including an effort to demonstrate what we believe are implications of denying particular constructions of Trinitarian doctrine.

For example (to use an illustration distinct from Theology Proper), I am convinced that believers’ baptism by immersion is the only biblical baptism. I remain thoroughly unconvinced by all the various extrapolations used to support infant baptism; I do not conclude (unless they state it themselves) that practicers of infant baptism deny the Spirit’s sovereignty in regeneration. Certainly they do not fall outside the pale of true Christianity, nor are their local congregations not true churches. I would contend that their local assemblies are necessarily, not just pragmatically, corrupt to some degree because of the tendency of a mispracticed ordinance; but they are still real Christian churches. And it seems to me, that the New Testament ordinance of baptism is much easier to understand, explain, and accept than some of the more intricate extrapolations we make as we seek to give an increasingly robust expression to the being and attributes of God.

Without doubt, the doctrine of God is intensely more central to a definition of orthodox Christianity than certain points of ecclesiology, but also it has a more forbidding aspect, is more filled with mystery, and so must evoke as much humility as it does intense scrutiny when brothers are privileged to explore the mystery together.

Eternal Generation

Nevertheless, I would seek to convince the exegetical theologian who has affirmed the Trinity in terms mentioned above that eternal generation has excellent credibility given its theological coherence, its exegetical fullness, and from the standpoint of the witness of the church universal. In illustrating the historical consent to this doctrine, we acknowledge the careful work of Athanasius and the Cappadocians whose views were summarized well by Basil’s statement, “We are not speaking of brothers; we are acknowledging Father and Son. There is identity of ousia since the Son derives from the Father, not made by a command, but begotten from his nature.” The relevant part of the Creed of Nicaea in this discussion stated: “And in one Lord, Jesus Christ, the Son of God, begotten from the Father, only-begotten, that is, from the substance of the Father, God from God, light from light, true God from true God, begotten not made, of one substance with the Father, . . . came down, and became incarnate and became man.” If the Son is begotten from the Substance or nature of the Father, as stated by the Nicene Creed (and as is so with all sons of all fathers), then in the case of a being whose essence is eternal the begetting must be eternal. It cannot be wrong to say, as Basil does say, that the “Son exists in full godhead as the living Word, the offspring of the Father.”6

Arius identified begetting with creating. Nicene orthodoxy, including the extended defense by Athanasius and others, rightly saw these two ideas as quite distinct and set it forth in perhaps the most succinct and important polemical assertion ever contrived, “begotten, not made.” Since the Son is begotten of the nature of the Father, he necessarily is of one essence with the Father. Arius argued for synonymity of beget and create in order to protect the singularity of God by denying the essential deity of the Logos. Some of our contemporary orthodox brothers, reflecting on modern etymological studies of Greek, have concluded that monogenes has nothing to do with begetting but means unique. They have not, however, adopted Arius’s concerns or conclusions, but, on the ground of a more full exegesis of related texts, affirmed the conclusions of Nicea of a single essence of deity manifest in three persons. They embrace Nicene orthodoxy but do not employ the argument based on eternal generation. In my opinion, they have limited the doctrinal formulation to an overstrictly conceived biblical field, omitting several relevant ideas.

I look at some Baptist witnesses to this doctrine. My good friend John Gill in his admirable defense of eternal generation believed that without this doctrine one might as well surrender to tritheism or modalism. I would seek to demonstrate that such an entailment makes a coherent argument, but would not accuse my dialogue partners of either error, if they clearly denied them.

The Philadelphia Association felt strongly the connections this doctrine has with the entirety of Christian doctrine. In it exposition of chapter 2, Samuel Jones wrote that Jesus was the only begotten of God, not due to the incarnation, nor the resurrection, nor in light of the mediatorial offices, but “that he was the only begotten Son of God by eternal generation, inconceivable and mysterious.” When an older member of one of the churches wrote some pieces questioning its veracity, he later confessed his error, and reaffirmed the doctrine. “We desire,” the Association responded, “that all our churches would take notice thereof, and have a tender regard for him in his weak and aged years, and in particular, of that great truth upon which the Christian religion depends; without which it must not only totter, but fall to the ground.” They printed the note of recantation and reaffirmation, by the man, Joseph Eaton.

I freely confess that I have given too much cause for others to judge that I contradicted our Confession of faith, concerning the eternal generation of the Son of God, in some expressions contained in my paper, which I now with freedom condemn, and am sorry for my so doing, and for every other misconduct that I have been guilty of, from first to last, touching the said article, or any other matter.”7

My personal doctrinal defense goes something like this. I believe that the doctrine of eternal generation (as well as double procession of the Spirit) is a necessary consequence from the very ideas of Father and Son as persons in the Godhead. It provides a consistent principle of interpretation for an abundance of Scriptures, and gives a coherent conceptual framework for maintaining unity of essence and distinction of persons in the Trinity. If the Son is eternally Son, then he must be eternally generated. The mode of existence relating and distinguishing fathers from sons in Scripture is generation (Genesis 5:3, 6, 9, 12). Fathers do not create sons but give rise to them from their nature. Our sons follow us in time because we are temporal creatures, but they still are of our nature. God’s Son, as generated must share his nature and thus must be eternal, and thus eternally generated.

Biblically, when God is referred to as the “Father of our Lord Jesus Christ,” this must refer to their eternal relationship for the Father is not the Father of the human nature of Christ (Colossians 1:3; Ephesians 1:3; Romans 1:1-4; 1 John 1:3). First John 5:18 refers to the one who keeps us as “the one begotten of God” and identifies him as the true God and eternal life. This appears to be a clear reference to begottenness as eternally operative in distinguishing between Father and Son in person while maintaining unity of essence.

The words “Son” and “Son of God” appear in an absolute sense as the one who was sent in that he exhaustively knows the Father, perfectly executes the will of the Father, occupies the same sphere of existence as the Father, and receives his self-existence from the Father. The title of identification, Son, refers to his pre-existing status in the event of his being sent, his appearing: “the reason the Son of God appeared was to destroy the works of the devil” (1 John 3:8); “We know that the Son of God has come” (1 John 5:20); “If what you heard from the beginning abides in you then you too will abide in the Son and in the Father” (1 John 2:24); “But of the Son he says, ‘Your throne O God is forever’” (Hebrews 1:8 where the point is that sonship and deity are identical); “When the fullness of time had come, God sent forth his Son” (Galatians 4:4). “All things have been handed over to me by my Father, and no one know the Father except the Son and anyone to whom the Son chooses to reveal him” (Matthew 11:27); “For as the Father hath life in himself, so hath he given to the Son to have life in himself” (John 5:26); “And the Father himself, which hath sent me, hath borne witness of me” (John 5:37). As a distinctly identifiable person, the Son receives from the Father not only a task to execute by his infinite power and through the mystery of his incarnation, but his interminable self-existence (“life in himself”). It seems to me that only his begottenness explains this.

The idea of firstborn relates to the generation of the Son. The writer of Hebrews (1:5) cited Psalm 2:7 “You are my Son; today I have begotten you.” This citation in the Psalter refers to the eternal decree by which the nations that oppose the Son will be brought low. They vaunt themselves against him but they do not realize that it had already been decreed that God’s Son would rule the nations: “I will declare the decree: the Lord hath said unto me, ‘Thou art my Son; this day have I begotten thee. Ask of me, and I shall give thee the heathen for thine inheritance, and the uttermost parts of the earth for thy possession” (Psalm 2:7, 8). This was the decree as established in eternity in which the Father addressed his Son in terms of begottenness. “This day” in relation to the time of the decree means the co-existent eternity of Father and Son. The text specifically ties his sonship to his begottenness. To his eternally begotten Son, the Father promised the subduing of all nations through the work of redemption covenanted within the triune God as the means by which “every knee shall bow, . . . and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father” (Philippians 2: 10, 11).

In Hebrews 1, the ordering of the argument begins with the decree, proceeds through the incarnation, the righteous life, and his rule over all, because, not only has he created all things, but he has perfectly executed the work of redemption. The word that is used to speak of his identity as he came into the world is “firstborn” (Hebrews 1:6). He, as firstborn, is brought into the world that he created and has the rights of the firstborn over it, for he is the Son of God, eternally the firstborn. Also, because of his redemptive work, he has the rights of the firstborn over the church, which he has redeemed with his own blood. His position as the Son, eternally generated, works out in his being the “first born of [over] every creature,” (Colossians 1:15) and he became head of the church in that he is the “firstborn from the dead.” While it is true that the particular rights spoken of come only because the Son assumed both the nature and obligations of true humanity, the dignity, honor, and status by which he is over the church and over creation comes from his rights as firstborn, the uniquely and eternally generated Son. The rights of the firstborn in Old Testament law are built on the eternal relation between the Father and the Son as one of eternal generation. Our being sons by adoption and through regeneration gives us a likeness to Christ in increasing measure so that he might be the “firstborn among many brethren” (Romans 8:29; Colossians 3:10). The 2LC rightly affirms, “the Son is eternally begotten of the Father.”

Eternal Submission of the Son

At the same time, eternal generation entails eternal submission of the Son to the Father. This submission is both natural and voluntary. It is natural because it involves one of several aspects of functions intrinsic to the Father/Son relationship. It naturally involves equality of essence (Genesis 5:3); it naturally involves reciprocity of love (Genesis 22:2; John 14:21, 31; 17:23, 24; Colossians 3:14); it naturally involves perfection of knowledge of shared essence and respective distinctive incommunicable properties. For our purpose we focus on its involvement naturally of submission.

Charles Hodge stated it this way:

The speculative objections to this doctrine of eternal sonship have already been considered. If Christ is Son, if He is god of God, it is said He is not self-existent and independent. But self-existence, independence, etc., are attributes of the divine essence, and not of one person in distinction from the others. It is the Triune God who is self-existent and independent. Subordination as to the mode of subsistence and operation, is a Scriptural fact; and so also in the perfect and equal Godhead of the Father and the Son, and therefore these facts must be consistent. In the consubstantial identity of the human soul there is a subordination of one faculty to another, and so, however, incomprehensible to us, there may be a subordination in the Trinity consistent with the identity of essence in the God head.8

J. P. Boyce cited that passage in Hodge approvingly as part of his answer to this proposal: “Even if there be inequality relative to each other as persons, because of the respective relations, this would no more require one to be an inferior God to the others, than the three separate persons make necessary such a threefold distinction in the divine nature, as to constitute them three Gods.” He followed that by reasserting that the revelation of three persons is stated in the language of Scripture so as to determine that this “belongs to the essence and nature of God.” Having established unequivocally the singularity of essence of the three persons of the one God, Boyce observed, “It remains simply to inquire in what respects they differ from each other, and whether with the equality, relative to the divine essence, there co-exists any inequality of person, or any kind of subordination.9 Before his citation of Hodge, Boyce had reasoned through the ideas of same essence and distinction of person. “Such subordination of person, indeed, seems to be taught of the Son of God to his Father. But it is equality and sameness of nature, not of office, which makes the Son truly God.” The Son is truly God because “he is a true subsistence in the Divine essence. He does not cease to be such because the Father is officially greater than he, nor even because the Father bestows, and the Son receives the communication of the divine essence.”10

The commands of honoring one’s father and mother, of obeying one’s parents reflect a principle intrinsic to the Trinity of the submission of the Son to the Father. Submission of person does not entail difference or inferiority of essence. We choose the word submission, for etymologically it speaks of the fitness of the Son’s being the sent one. Missio denotes sending as a representative and under the authority of another. The Son has been commissioned (“The word that you hear is not mine but the Father’s who sent me.”) He is the emissary to execute all that is objectively essential to the redemption of the elect. He is submissive in the natural relation of Father and Son and thus the perfect congruity of his being the one under the covenantal arrangement to be sent, while the Father sends. “And this is eternal life,” so Jesus prayed to his Father, “ that they may know you the only true God, and Jesus Christ whom you have sent” (John 17:3) “O righteous Father, even though the world does not know you, I know you, and these know that you have sent me” (John 17:25). That Jesus is the sent-one reflects the potentiality resident within the eternal relation of Father and Son.

Those who accept the doctrine of eternal generation should accept eternal submission. If not, they omit one of the chief means of expressing the order implied in that inter-personal, inner-trinitarian relationship consistent with the natural moral goodness of the submission of children to parents (Exodus 20:12; Ephesians 6:1,2).

As there are three persons in the Trinity without a contradiction of singularity and simplicity of essence, so there are three natural and necessary self-conscious expressions of the single essence, eternally active, and intrinsically manifest without any division in the divine will. Each person, however, manifests the immutable, unalterable divine will in a way fitting for the distinction of person, but perochoretically related. Boyce relates the divine will to the three person of the Trinity. “Though it is true that the Father wills to beget the Son, and the Father and Son will to send forth the Spirit; yet the will thus exercised, is not at mere good pleasure, but it results necessarily from the nature of God, that the Father should thus will the begetting, and the Father and the Son the sending forth.”11

Each person sets forth the singularity of the decree of God with an eternal and immanent consciousness of and consent to all the economic provisions of the decree, having naturally and eternally assumed such roles in that decree that reflect and maintain the personal distinctions necessary to the Trinity. The decree arises from and perfectly fits the personal distinctions resident within the Trinity, and nothing naturally attached to the personal distinctions involves a subordination of essence. Surely the Son has eternal consciousness that he is not the Father and that his fitting operation in the eternal covenant of redemption is distinct from that of the Father and of the Holy Spirit. No division exists in the will of the one God, but the Son and the Spirit have full consciousness that their expression of that will is unique to their eternal personhood. A sentence, therefore, like that affirmed by the Philadelphia Association in giving an exposition of the three-personed aspect of God is acceptable terminology in this discussion: “They have each of them understanding and will.”12

Several passages in Holy Scripture indicate individuated personal expressions of the univocal will set forth in the eternal decree of redemption of the triune God. “Jesus said to them, ‘My food is to do the will of him who sent me and to accomplish his work” (John 4:34). “Truly, truly, I say to you, the Son can do nothing of his own accord, but only what he sees the Father doing. For whatever the Father does, that the Son does likewise” (John 5:19). “For as the Father raises the dead and gives them life, so also the Son gives life to whom he will” (John 5:21 [He cannot give life to whom he will in the human nature but only in the divine]). “I can do nothing on my own. As I hear, I judge, and my judgment is just, because I seek not my own will but the will of him who sent me” (John 5:30). “For the works that the Father has given me to accomplish, the very works that I am doing, bear witness about me that the Father has sent me” (John 5:36). “All that the Father gives me will come to me, and whoever comes to me I will never cast out. For I have come down from heaven, not to do my own will but the will of him who sent me. And this is the will of him who sent me, that I should lose nothing of all that he has given me, but raise it up at the last day. For this is the will of my Father, that everyone who looks on the Son and believes in him should have eternal life, and I will raise him up at the last day” (John 6:37-40; cf 1 John 5:18, “He who was born of God protects him.”)

Doctrinal syntheses that may be made from these passages included the following.

- The Son of God has consciousness that he is the one sent by the Father, that he has a task assigned by the Father, a people given to him by the Father, and that he is fully capable, as of the essence of the Father, of executing all of this. His submission in every case is at the same time a confession of his consciousness of equality of essence and unity of will.

- When the Son, in his incarnation, speaks of “my own will,” does he refer only to the human will or does he include the divine will as uniquely expressed in his personhood as Son. If there is no such unique expression of the divine will through the Son, then in what manner did he consent as Son to be sent by the Father? If we claim that there is no fitting personal appropriation of the divine will by the three persons of the Trinity, Christ could just as easily have indicated on all these occasions, “I have come not to do my own [human] will but the will of my divine nature.” This is undoubtedly true in the final sense, but not fitting for the manner is which the will is appropriated within the eternal personal relations of the Trinity. Also, if there is no distinct filial expression of the divine will, does his divine will mean that in some sense, because the divine nature and the human nature of Christ are neither confused nor divided in the Son, that the Father and the Spirit have also willed to participate materially, beyond perochoresis, in the incarnation?

- His being sent does not refer to the conception of his human nature by the Holy Spirit but to a pre-incarnate arrangement. Jesus refers to both of these in a statement to Pilate, “For this purpose I was born and for this purpose I have come into the world” (John 18:37).

- He refers to this arrangement as doing the “will of him who sent me.” Although it does not differ in any particular from his own will as the Son of God, the one sent was aware prior to his being “conceived of the Holy Spirit, born of the virgin Mary,” that he came into the world under that pleasure and authority of the Father’s, His Father’s, will.

- His own functions as God flow from his unity with the Father and fully express the character and power of the Father but also may be spoken of as the result of his own will (“For as the Father raises the dead and gives them life, so also the Son gives life to whom he will” John 5:21); “No one knows the Father except the Son and anyone to whom the Son chooses to reveal him” Matthew 11:27).

- That which drove him in all the works of his entire person, both his humanity and his deity, was the successful completion of the work the Father had given him to do, to live in complete alignment with the Father’s will, as a manifestation of the Father’s will in particular, though it did not differ from his own will as immanently expressed in the eternal covenant of redemption.

- This work of the Son arises, not as an arbitrary assignment disconnected from the eternal mode of relation of the three persons of the one God, but as a fitting and accurate revelatory manifestation of the immanent operations of personhood in the Trinity.

Not only is there no contradiction between submission of the Son and equality of essence, but the eternal generation of the Son naturally involves a fitting expression of submission in relations among equals. The word “subjection” seems fitting as per 1 Corinthians 15:27, 28, indicating that at the completion of all the provisions of the decree as announced in Psalm 2:6-9, the glory of the triune God will have eternal manifestation as seen in the fitting arrangement of personal relations after completion of personal roles in the covenant. As Gill noted, “It will be then seen that all that the Father has done in election, in the council and covenant of peace, were all to the glory of his grace; and that all that the Son has done in the salvation of his people, is all to the glory of the divine perfections: and that all that the Spirit of God has wrought in the saints, and all that they have done under his grace and influence, are all to the praise and glory of God, which will in the most perfect manner be given to the eternal Three in One.”13

Present Economy Implies Eternal Fitness and Propensity

Are there necessary and fitting connections between God’s opera ad intra and his opera ad extra? Do the Father and the Son and the Spirit operate precisely in the same spheres and in the same ways in the opera ad extra? No. Is this because, as they exist eternally and necessarily as three persons in one God, these eternal personal distinctions operate ad extra in a way consistent with their existence ad intra? I would say yes, and would see this as an expression of the divine simplicity, not a Unitarian simplicity, but a Trinitarian simplicity.

This reality is captured in the phrase opera certo modo personalia. This means that there are certain ways in which the works of God terminate on one person more fittingly than on another. Was the eternal disposition of the Son to empty himself in the event of the incarnation for the work of mediation out of harmony with his personhood, or in harmony with his personhood, or, in an absolutely indifferent manner, having no relation to the perfect moral propensities of the unchanging divine nature? Neither disharmony nor indifference is possible, so the role undertaken was in harmony with his eternal personhood as the Son. Consenting to incarnation would have been out of harmony with his personal mode of existence for the Holy Spirit.

As stated above the reality of eternal submission is both natural and voluntary, thus godlike and necessary. The word natural denotes an internal Trinitarian prosopological relation. Obviously the relation is supernatural, if one speaks vis-a-vis the created order, but “natural” if speaking of personal relations within the one essence of deity. The fact that such is natural within the godhead means also that it is necessary. Further, this submission is one of the “several peculiar relative properties” operative in the personal relations of the Trinity.

Voluntary means that every ad intra personal relation is expressive necessarily of the divine will. Boyce visits this idea as a general statement in a discussion of the personal relations within the Trinity. “It is because God is one in three persons, and because the three persons are one God, that he thus makes himself known to us.” His threeness in the biblical record reflects his eternal existence and sheds light on the essential, eternal, voluntary engagements of persons. “Though it is true that the Father wills to beget the Son,” Boyce continued, “and the Father and Son will to send forth the Spirit; yet the will thus exercised, is not at mere good pleasure, but it results necessarily from the nature of God.”14 This will is not like that exercised toward “various purposes that he might form,” but that “by which he necessarily wills his own existence”

That such a will toward himself exists eternally is the foundation of his will in all other things. If no such thing as “will” existed in God ad intra there could be no will exerted ad extra. Augustine stated truly that God’s substance is not changed by time or any other thing and that his will is intrinsic to his substance. “Wherefore,” so he reasoned, “He willeth not one things now, another anon, but once and for ever He willeth all things that He willeth; not again and again, nor now this, now that; nor willeth afterwards what He willeth no before, nor willeth not what before he willed.”15

If this were not the case, there could be nothing of the sort described by Paul as “the plan of the mystery hidden for ages in God who created all things” nor the manifestation of it “according to the eternal purpose that he has realized in Christ Jesus our Lord” (Ephesians 3:9, 11). Paul’s explanation of the certain efficacy of the prayers of the elect and their absolute safety in the providential purpose of God would be nonsense when it is set up with this assurance: “And he who searches hearts knows what is the mind of the Spirit, because the Spirit intercedes for the saints according to the will of God” (Romans 8:27). That eternal essential will by which the triune God glories in his own existence gives foundation to the will and operations manifest in the purpose toward the world he created before he created it. God the Father knows the mind of the Spirit, and the Spirit intercedes according to the will of God; though none of the stated relationship are at variance, nor indicating more than one will in God, nor any advancement in understanding within any of the persons of the Trinity, they do show that the distinct operations according to the eternal purpose are consistent with distinct personal appropriations of that will in eternity.

If one suggests that begottenness is the only property that can be ascribed to sonship, and that double procession is the only distinct property of the Holy Spirit, he affirms only a mode of being and not attributes of being. Does simplicity really demand that we ascribe no properties to any person of the Trinity? And unless one wants to deny that God “works all things after the counsel of his will,” then any distinct provision of such operations undertaken by any person of the Trinity, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit must be naturally and willfully, voluntarily, assumed as the fitting appropriation of the single will of God by that distinct personal subsistence.

Neither the absolute unity of the divine will nor the simplicity of his internal being and operations is challenged or disrupted in seeking to be truly Trinitarian. Certain radical and rationalistic applications of simplicity drive the thinker toward an arid and lonely Unitarianism and make him squelch a fully-engaged and dynamic interaction with the data of Scripture. Neither the Arians nor the Socinians could overcome the apparent contradiction between the threeness of persons and the uniqueness of godness. Orthodoxy has avoided the apparent contradiction by positing a distinction between the concept of persons, of which there are three, precisely three, and necessarily three, and the concept of nature, essence, and being of which there is one, necessarily subsistent in three persons.

Since orthodoxy has preserved the biblical distinction between the essential attributes of the one true God, and the distinctive properties of the persons (which threeness is presented as absolutely necessary for the existence of God, so that his threeness is as essential as his oneness), no contradiction exists, but a fertile field for an expansive discussion challenging the mind and enlivening the spirit and the affections is set before all disciples of truth. John Brown placed the issue in a vigorous conceptual framework: “It is evident, from the independence, simplicity, eternity, and unchangeableness of the divine nature, that in whatever form it subsists [italics mine], that form must be a necessary perfection or excellency of it, without which it could not at all exist. The personal properties of these persons being thus as absolutely necessary, as the existence of the divine nature itself, and each having that whole nature which necessarily subsists in such persons, as above related to one another, there neither is, nor can be, an inferiority in, or dependence upon, one person, more than another.”16 The “personal properties” are as “absolutely necessary” to the being of the God who exists as is his singularity of essence.

A Personal Stewardship of the Truth

We always are teetering on the edge of error on this issue no matter how guarded, chastened, and careful our language is. Every theologian has seen it in his day and, ironically, contributes to it while he seeks to escape it. None of us can say everything at once, and so the aspect of truth that we seek to emphasize may seem enlarged, out of proportion, and, thus, wrong. Calvin noted in his discussion of the expressions of “Trinity” and “Person” in Institutes I.xiii.3, “For thus are we wearied with quarrelling over words, thus by bickering do we lose the truth, thus by hateful wrangling do we destroy love.” The great confessionalist Princetonian Samuel Miller issued caution in this sphere of doctrinal labor:

On the one hand, if such absolute uniformity in the mode of explaining every minute detail of truth is contended for, with the rigor which some appear to consider as necessary; if men are to be criminated, and subjected to discipline, for not expounding every doctrine contained in the Confession of Faith in the same precise manner with every other subscriber who has gone before him; the church must inevitably be kept in a state of constant mutual crimination and conflict, and peace will be out of the question.17

The other hand, of course, is that we pay too scarce attention to the expressions we use and thus become slovenly in the way we speak of the most grand and preeminently important subject that confronts the human mind. The possibility of using words to propagate destructive error also challenges us to take caution and seek as much uniformity as possible in words and the definitions attached to those words. The confessional history that cultivates the language, while not authoritative, nevertheless, is informative and provides a common vocabulary by which we may express ourselves meaningfully. We should embrace such a historically-anointed common language knowing that it will render more accurate understanding in dialogue than otherwise would be possible. It is helpful also to realize that such language was not chosen arbitrarily as the result of one theological dialogue, but from decades, even centuries, of sorting through ideas and their implications and complications. Those pastors, theologians and controversialists engaged in this process were deep students of the Bible and the formulas thus resulting were developed in light of giving the most accurate synthesis of the full biblical witness.

We must not think, however, that we exhausted the full biblical witness in ascribing to both our ecumenical and our denominational confessions. The Bible still is living and active, and we still must work on the triadic task of exegesis, theological formulation, and application. The Bible is a big book that constantly is pressing us toward the edges of possible comprehension. As stewards of the mysteries of God we must be faithful to all that we can perceive that it means.

Receiving both encouragement and warning from those candid admissions, I submit just a bit more analysis. When one focuses more intensely, or perhaps exclusively, on the singularity of essence and divine simplicity, the language of subordination, or submission, or subjection borders on an implicit subordinatonist Christology. Clearly some orthodox theologians conclude that eternal subordination of the Son, or perhaps any distinctive incommunicable property, challenges the simplicity of God. Any concept of necessary roles within the Trinity ad intra is inconceivable, so they argue. While we do not want to assert anything that is by definition impossible, the idea of what is conceivable or inconceivable must not be closed too tightly.

The concept of one God eternally existing as three persons stretches the borders of what might be conceivable. It is a matter of divine revelation. Scripture is filled with descriptions of discreet functions that indicate personal properties which will be manifest according to the will of God as fittingly expressed by each of the persons. For example, “He who did not spare his own Son, but delivered him up” shows a particular fitness in that manifestation of will by the Father that would not be fit, or even possible, for the Spirit. Nor does it appear that the Spirit’s consent to become a man and take on human flesh would be consistent with his eternal mode of existence, and thus such a will on his part is virtually inaccessible, while such a will fully consists in the personal properties of the Son. Manifestations of will consistent with personal properties may, in one sense, be seen as a voluntary personal property that does not divide the will but maintains the intrinsic integrity of each personal subsistence and thus the divine simplicity and substantial unity. Interestingly, in Calvin’s refutation of Sabellianism, he observed, “To shatter the man’s wickedness the upright doctors, who then had piety at heart, loudly responded that three properties must truly be recognized in the one God”18

Without revisiting my preference for the word “submission” with all the reasons given already, arguments to the contrary have not, to my mind, given any compelling reason that submission cannot be an eternal incommunicable property in the eternally generated Son. God is the only being who exists absolutely; he alone is being in itself in that he never changes and nothing superfluous exists in his nature. He is simple and without accidents, that is, nothing is conjoined with him in his being that can be withdrawn or changed or is merely incidental to his essence. He is pure, immutable, infinite, and absolute being. This every Christian should affirm joyfully and in a spirit of worship.

His substance, and thus will, never changes in any of his relations either in eternity or in his purposefully directed engagement with time, space, and other substances. We can safely assume, therefore, that the postures manifest in those relations conform to his eternal substance, his simplicity, his immutability, the essentiality of every operation of his will. If it is true then, and it is, that God is “without accidents,” then nothing resident within the dynamic fellowship and glory of the Godhead is a mere appendage, and even economic covenantal relations assumed “before the foundation of the world” speak of something that is essential, not accidental, in the being of Trinitarian relations.

When we learn, therefore, that God the Father “has blessed us in Christ with every spiritual blessing in the heavenly places, even as he chose us in him before the foundation of the world” (Ephesians 1:3, 4), we find out something about the simplicity of God that includes the particular offices of each person of the Trinity in eternal relations. When we learn that God has saved us in accord with “his own purpose and grace which he gave us in Christ Jesus before the ages began” (2 Timothy 1:9), we peer into eternity and see divine simplicity manifest in covenantal roles assumed in accord with essential attributes of the triune God, and non-accidental incommunicable properties of each person of the Trinity.

When we learn that eternal life was “promised before the ages began” (Titus 1:2), we may safely assume that such a “promise” was consistent with the eternal relations of the three persons. Everything essential to effect eternal life through the separate but equally divine and perichoretically effected operations of Father, Son, and Spirit were presumed in the promise. Revealed roles, therefore, were not assumed as accidents, something prosopologically extraneous, but in accord with immutable divine attributes that include the discreet operations of each person of the Trinity in the one indivisible operation of God.

When we learn that Christ Jesus “did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped,” that he assumed in eternity co-terminous with the existence of the eternal pactum salutis, the temporal evacuation of the display of the glory of his deity, and that his so assuming this principle of the incarnation was taken for himself alone arising from an incommunicable property of his eternal existence as Son, we learn something about divine simplicity.

While by perichoresis we receive the revealed truth that the Father “has caused us to be born again” (1 Peter 1:3), and that the “Son gives life to whom he will” (John 5:20), we at the same time recognize that by office peculiar to himself, “It is the Spirit who gives life” (John 6:63). This is intensified by the Bible’s expanded testimony that “the Spirit is life because of righteousness” (Romans 8:10), and “if by the Spirit you put to death the deeds of the body, you will live” (Romans 8:13), and that “unless one is born of water and the Spirit, he cannot enter the kingdom of God [and] that which is born of the Spirit is spirit” (John 3:5, 8), and that we are initiated existentially into divine mercy “by the washing of regeneration and renewal of the Holy Spirit.” Knowing these things by divine revelation, we concede that there is a particularity in the office of the Spirit fitting to him prosopologically in a way that is not so of the Son and the Father. Though only an ad extra manifestation, such operations reflect an ad intra potential of an eternal propensity in God.

Though ad intra God has no parts, he can, and in fact must, manifest his simplicity in parts as he deals with his creation which does consist of parts. Different moral states require distinct and justly operative acts of God toward each moral being in particular—mercy, grace and forgiveness toward some and wrath, fury, tribulation, and distress toward others—all of them as distributions of his simple goodness, their capability of partitive distribution in no way contradicting or compromising divine simplicity.