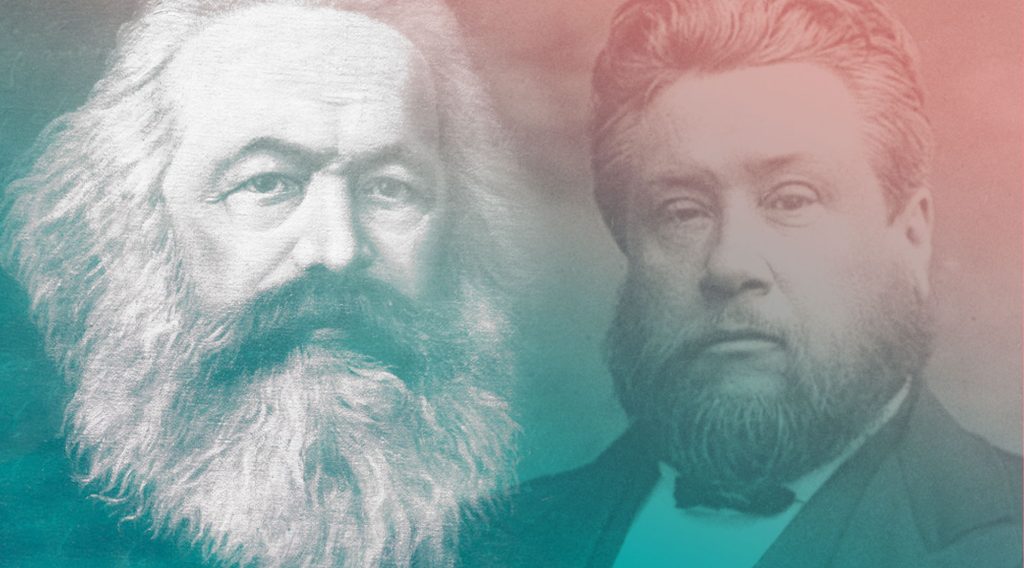

Karl Marx, an apostle of evil, and Charles Spurgeon, the “Prince of Preachers,” were evangelists with messages that couldn’t have been more different—and they lived in the same city at the same time.

My next book (after this one) will focus on two men whose graves I have visited many times. The first lies in North London at Highgate Cemetery. Among the fifty-three thousand graves there, one finds a few notables: Michael Faraday, inventor of the electric motor, and Adam Worth, the real-life basis for Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s evil Moriarty in the Sherlock Holmes stories, are two. Most notable of all is the resting place, a monument really, of Karl Marx. Though Prussian, Marx lived in London the last thirty-four years of his life. There he refined his radical secular ideology and produced Das Kapital, setting loose upon the world ideas that have wrecked half of it and now threaten to wreck the other half.

The second lies in South London at West Norwood Cemetery. Among the forty-two thousand graves there, one also finds a few men of renown: Paul Julius Baron von Reuter, founder of the global news organization of the same name, and Hiram Maxim, inventor of the first portable fully automatic machine gun, are interred here. Perhaps more illustrious than either of these is the grave of Charles Spurgeon. The “Prince of Preachers,” Spurgeon was the nineteenth-century’s British equivalent of Billy Graham. He pastored what was allegedly the largest church congregation in the world.

It is extraordinary to me that both Karl Marx (1818-1883) and Charles Spurgeon (1834-1892) lived and worked in the same city at the same time. Both were, in a sense, evangelists contending for the souls of men with their competing visions of humanity. Moreover, each was at the height of his powers at the same time as the other. While Marx was preaching salvation through bloody revolution, Spurgeon, on the other side of the city, was preaching salvation through the blood and grace of Jesus Christ.

The London of Marx and Spurgeon was the center of world governance and epoch-defining ideas. With Queen Victoria’s missionaries to civilize it and her ministers, armies, and navy to rule it, the British Empire was at its zenith so that the sun literally never set upon it. Whether it was David Livingstone searching for the source of the Nile or Charles Darwin penning On The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, Britain was at the forefront of all that was considered progress.

But the Britain of this era convulsed with the problems endemic to massive social change. So much so, that an air of revolution lingered like some ominous storm gathering on the horizon, threatening to engulf this peaceful kingdom as it had intermittently done on the continent since the French Revolution in 1789.

The island nation was in the throes of the bare-knuckled phase of the Industrial Revolution which brought with it a special kind of human degradation. The urban poor crowded the slums and populated the novels of Charles Dickens. Child labor laws were in their infancy. Black factory smoke choked the air and coal dust filled lungs.

It was into this combustible atmosphere that Karl Marx stepped. The man with a beard so wild that it might have landed him on a Kansas album cover were he born a century later, had revolution on his mind when he moved from Paris to London in 1849. Of course, revolution had always been on his mind. Marx had sought the overthrow of governments throughout Europe, and in the ensuing turmoil of 1848, he was forced to flee the continent.

Once in London, Marx spent his days at the British Museum preparing his magnum opus, Das Kapital, a critique of capitalism that could fill a sizable pothole. Although he fashioned himself as a scholar, he was more of a dilettante, a dabbler in scholarly activity. A scholar begins with a tentative thesis and allows the facts to dictate his conclusions. He is, in other words, committed to the truth. In sharp contrast to this methodology, Marx—like “woke” media and “woke” policies and “woke” academia—began with a conclusion and worked backward from it, facts be damned.

“Communism abolishes eternal truths,” he declared openly in The Communist Manifesto (1848). “It abolishes all religion, and all morality, instead of constituting them on a new basis …”

In another passage of that dangerous little book, he says:

Abolish the family! The bourgeois family will vanish as a matter of course when its complement vanishes, and both will vanish with the vanishing of capital…. The bourgeois clap-trap about the family and education, about the hallowed co-relation of parent and child, becomes all the more disgusting, the more, by the action of Modern Industry, all family ties among the proletarians are torn asunder, and their children transformed into simple articles of commerce and instruments of labour.

Much as Mein Kampf (1925) would be a bald statement of Hitler’s intentions should he ever attain power, The Communist Manifesto is likewise clear in stating the objectives of communists (i.e., socialists) should they ever attain power. No one could justly say he was not forewarned. (So, it is, too, with Black Lives Matter, where one finds all of this restated in oblique terms on their website. Note: The referenced article has since been taken down. The link points to the original article as archived at web.archive.org.)

Lazy and like socialists of any era, Marx did not mind accepting monetary handouts from wealthy capitalists while criticizing the means by which they had acquired the wealth. (Black Lives Matter, a Marxist organization, has received almost $2 billion in corporate contributions.) Marx was allergic to work, it seems, and never held a steady job. Even as he extolled the evils of capitalist industry, there is no evidence he ever visited a factory at any point in his miserable life. His mother bitterly complained that she wished that her son would “accumulate capital instead of just writing about it.”

In the spirit of other would-be revolutionaries before and since, Marx was a Manichean who divided the world into two camps: the Revolution and its enemies. These were simply identified as those who agreed with this dogmatic Prussian and those who did not. The former were considered intelligent and enlightened; the latter were berated in racist and anti-Semitic rants. Marx attacked one opponent as a “Jewish nigger.” One can well imagine Marx fitting right in with the modern “cancel culture” Twitterati. He saw capitalism as a poison perpetrated on humanity by Jews and he hated them for it, though it seems anti-Semitism came naturally to him. To read Marx’s personal letters or published works is to encounter a bitter, evil mind concealing a hate in what he (and others) promoted as a noble vision of humanity.

But a noble vision it is not.

That vision of human dignity and salvation found expression in the preaching of Charles Spurgeon who burst upon the London scene in 1853. Spurgeon was merely 20 years old when he was appointed pastor of a congregation at the New Park Street Chapel in south central London. Soon, his earnest, passionate messages were attracting enormous crowds, requiring services to be moved to the largest public gathering space in London, the Royal Surrey Gardens Music Hall. A letter published in The Times describes what would become a familiar occurrence for the next three decades:

Fancy a congregation consisting of 10,000 souls, streaming into the hall, mounting the galleries…. Mr. Spurgeon ascended his tribune. To the hum, and rush, and trampling of men, succeeded a low, concentrated thrill and murmur, of devotion, which seemed to run at once, like an electric current, through the breast of every one present, and by this magnetic chain the preacher held us fast bound for about two hours. It is not my purpose to give a summary of his discourse. It is enough to say of his voice, that its power and volume are sufficient to reach everyone in that vast assembly; of his language that it is neither high-flown nor homely; of his style, that it is at times familiar, at times declamatory, but always happy, and often eloquent; of his doctrine, that neither the ‘Calvinist’ nor the ‘Baptist’ appears in the forefront of the battle which is waged by Mr. Spurgeon with relentless animosity, and with Gospel weapons, against irreligion, cant, hypocrisy, pride, and those secret bosom-sins which so easily beset a man in daily life; and to sum up all in a word, it is enough to say of the man himself, that he impresses you with a perfect conviction of his sincerity.

So popular was he that in 1857, at the request of Queen Victoria, the twenty-three-year-old Spurgeon electrified a crowd of twenty-four thousand at the Crystal Palace with his sermon about the first day of creation.

Although there is no indication that Marx and Spurgeon ever met, one was almost certainly aware of the other and the irreconcilable nature of the messages each proclaimed. Both achieved fame in his own lifetime, and while Spurgeon’s fame eclipsed that of Marx during the 1850s and 1860s, Marx’s message of secular salvation gained in prominence after the publication of the first volume of Das Kapital in 1867, and especially after the failure of the Paris Commune in 1871. And it is in this post-Paris Commune period that Spurgeon begins to take note of Marx’s philosophy if not the man himself.

It would be wrong to say—as many preachers do—that addressing matters of politics falls outside of the purview of the clergy. Of no other sphere of life do they say it. Regardless, Spurgeon certainly didn’t agree with this sentiment. Christianity isn’t merely an accessory to a man’s life; it should define it. Thus, a man’s politics are simply the outward manifestation of the convictions of his heart. Socialism, Spurgeon knew, was much more than an economic or political question. It is a spiritual question, if only because it denies the very existence of the spiritual. It is, as I have written elsewhere, atheism masquerading as political philosophy.

Spurgeon had, in fact, noted the dangers of socialism remarkably early in his ministry. In 1855 he warned of communists who wanted nothing less than “the real disruption of all society as at present established.” He asked the gathered, “Would you desire reigns of terror here, as they had in France? Do you wish to see all society shattered and men wandering like monster icebergs on the sea, dashing against each other and being at last utterly destroyed?”

But it is in the post-1871 period that he speaks more frequently and with greater urgency on the subject of socialism. In a sermon on Psalm 118 in June 1878, Spurgeon made a tentative prediction to his congregation:

German rationalism which has ripened into Socialism may yet pollute the mass of mankind and lead them to overturn the foundations of society. Then “advanced principles” will hold carnival and free thought [i.e., atheism] will riot with the vice and blood which were years ago the insignia of “the age of reason.” I say not that it will be so, but I should not wonder if it came to pass, for deadly principles are abroad and certain ministers are spreading them.

In a sermon on Isaiah 66 in April 1889, Spurgeon, recognizing that many had confused the Gospel of Jesus Christ with the cheap, secular knock-off proclaimed by Marx and his ilk, thundered from his pulpit:

For many a year, by the grand old truths of the gospel, sinners were converted, and saints were edified, and the world was made to know that there is a God in Israel. But these are too antiquated for the present cultured race of superior beings! They are going to regenerate the world by Democratic Socialism, and set up a kingdom for Christ without the new birth or the pardon of sin. Truly the Lord has not taken away the seven thousand that have not bowed the knee to Baal …

The latter-day gospel is not the gospel by which we were saved. To me it seems a tangle of ever-changing dreams. It is, by the confession of its inventors, the outcome of the period—the monstrous birth of a boasted “progress”—the scum from the cauldron of conceit. It has not been given by the infallible revelation of God—it does not pretend to have been. It is not divine—it has no inspired Scripture at its back. It is, when it touches the Cross, an enemy! When it speaks of Him who died thereon, it is a deceitful friend. Many are its sneers at the truth of substitution—it is irate at the mention of the precious blood. Many a pulpit, where Christ was once lifted high in all the glory of His atoning death, is now profaned by those who laugh at justification by faith. In fact, men are not now to be saved by faith but by doubt. Those who love the Church of God feel heavy at heart because the teachers of the people cause them to err. Even from a national point of view, men of foresight see cause for grave concern.

The reference to bowing knees is prescient given the events of our own time. But it must be noted where Spurgeon lays blame for the state of things. Like Francis Schaeffer a century later, he places it squarely on the men of his own vocation. As if to assail the heresy that would infect the pulpits of the Western world, Spurgeon speaks directly to the political climate. Indeed, if there were lines proscribing the lane in which he as a clergyman was to remain, he refused to acknowledge them. Like a charioteer in the Circus Maximus, he thrashed the fleet-footed horses carrying the Gospel he preached right across every lane of human endeavor, especially those that presumed to exalt themselves above God as socialism surely does.

Apart from Kim Jong-un, I have met and engaged the most famous atheists of this age. Like every one of them, Marx belonged to that category of men that Romans 1 calls “haters of God.” One simply does not set up idols and altars if he is anything else, and that is precisely what socialism is: a false god set up against the one true God in a great act of defiance, offering men a counterfeit version of salvation. Marx himself was not unaware of how easily some confuse the authentic for the false, and he sought to exploit it. “Nothing,” he wrote in The Communist Manifesto, “is easier than to give Christian asceticism a Socialist tinge.”

For this reason, Spurgeon combated Marx and his ideas just as the Apostle John had once opposed Cerinthus and Augustine had used his formidable intellect to confront Pelagius.

“Great schemes of socialism have been tried and found lacking,” Spurgeon inveighed in another sermon. “Let us look to regeneration by the Son of God, and we shall not look in vain.”

It is very likely that the preaching of Spurgeon, and others like him, prevented the violent Revolution in Britain that Marx sought. Ironically, that revolution would come in the unindustrialized Russia of 1917, when Vladimir Lenin would, at the cost of millions of lives, implement Marx’s unworkable ideas. That is in no small measure due to the fact that there was no viable church to critique the undeliverable promises of socialism.

According to Russian historian Orlando Figes, when Marx’s Das Kapital was approved for publication in Russia by the censors who forbade almost any political expression, the ideas therein were released into an ideological vacuum. By contrast, those same ideas were (rightly) subjected to withering attacks in Britain by those who saw them for what they were. In this sense, Christianity served as a bulwark against the barbarism that has accompanied Marxism everywhere—everywhere—it has been implemented.

Today the battle continues, but the battlefield has expanded to the entire world. Marxism morphs as it goes, disguising itself until it reaches our own time in the sheep’s clothing of racial equality and so-called “social justice.”

The Gospel, however, remains remarkably unchanged. Its power to transform societies is one of the most underrated benefits of Christian belief. Through the inward transformation of the individual, there is a corresponding outward transformation of society. This is what I call “The Grace Effect.”

No greater scam has been perpetrated on so many for so long than the lie that socialism, once adopted, will reorganize society along the lines of a utopia for all. Such political solutions have always failed, and this one has nothing but a history of catastrophic failure.

As Spurgeon so eloquently put it: “To attempt national regeneration without personal regeneration is to dream of erecting a house without separate bricks.”

This article was originally posted on www.larryalextaunton.com and is posted here with the Author’s permission.

Follow Larry Alex Taunton:

-

- Twitter | @larrytaunton

- Facebook | @larrytaunton

- Website | www.larryalextaunton.com