Over the last fifty years American evangelicals have been forced to address the question of biblical authority. In the early 1970s North American evangelicalism came dangerously close to theological apostasy. Many leaders had begun to drift away from their historic commitment to the authority of Scripture. Professors in prominent colleges and seminaries were becoming bold in teaching that the Bible contained many historical and scientific errors, but that this did not matter to the Christian faith. It looked like evangelical churches were going to follow the steps of mainline protestant denominations and drift into the sea of liberalism.

In his mercy, God raised up some leaders who saw and this trend and determined to sound the alarm. In 1977 the International Council on Biblical Inerrancy was formed. This council held several meetings and issued three statements, the most famous of which is the “Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy.” Over the decade of the eighties and into the nineties evangelicals engaged in what came to be called, “The Battle for the Bible.”

This battle raged hot within the Southern Baptist Convention. From 1979–1995, conservative church leaders who affirmed the inerrancy of Scripture stood against moderate church leaders who denied the inerrancy of the Bible. In God’s goodness and grace, both within the SBC in particular and the broader evangelical world in general, there was a renewed commitment to the absolute authority of God’s Word. Inerrancy won the day. Because of this, many then made the claim—and continue to say today—that the “Battle for the Bible” is over.

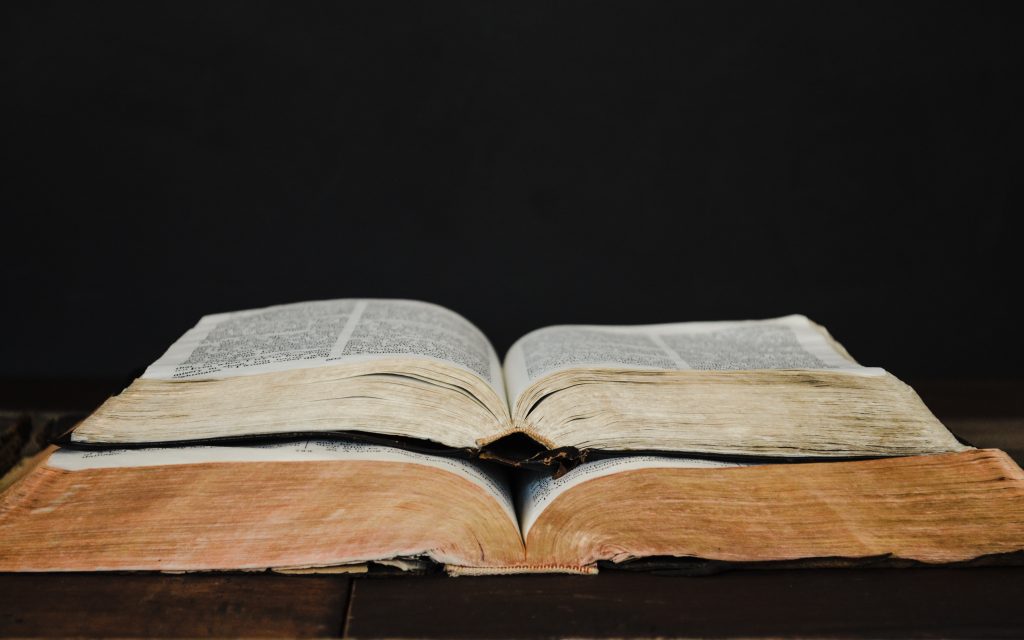

BUT, the Battle for the Bible will never be over. Granted, it is now widely recognized that to be an evangelical means to believe in the full, unwavering authority of the Bible. Though the authority of Scripture must always remain a key concern for us, it is no longer the most critical issue that confronts us. Today, the most important issue that confronts evangelicals is the sufficiency of the Scripture.

I first heard the late James Boice raise this concern more than 25 years ago. He later expressed his thoughts in his book, What Makes a Church Evangelical, in 1999. This is what he wrote (p. 20):

The issue I would pinpoint today is the sufficiency of God’s Word, meaning, do we really believe that in this book God has given us what we need to do all necessary spiritual work? Or do we think we have to supplement the Bible with other man-made techniques or devices? Consider the following areas of the church’s work:

- Evangelism. Do we need sociological techniques to do evangelism? Must we attract people to our churches by showmanship and entertainment?

- Sanctification. Do we need psychology and psychiatry for Christian growth? Are support groups essential?

- Discerning God’s will. Do we need extra-biblical signs or miracles for guidance? Does God speak to us “in our heart,” in a way that is just as important and real as the Scriptures?

- Impacting society. Is the Bible’s teaching adequate for achieving social progress and reform?

The question is no longer, “Is the Bible true?” (though that issue, along with the necessary implication of the final authority of God’s true Word, will never be irrelevant). Rather, today the most pressing question about the Bible for evangelicals is, “Is it enough?” The battle that rages around this question is a more difficult one to fight in many respects for this very reason: The denial of biblical authority was a frontal assault on the Christian faith. The issues were clearly marked out and the implications were obvious for all to see.

The denial of Scripture’s sufficiency, on the other hand, is a far subtler attack. It is harder to detect. Furthermore, this attack is being aided unwittingly by many who would never deny the Bible’s full authority but who, by their promotion of deceitful philosophies, are undermining its sufficiency for Christian faith and practice.

One such idea is “intersectionality,” which Rosaria Butterfield calls “the worldview du jour” and describes as “the belief that who you truly are is measured by how many victim-statuses you can claim, with human dignity only accruing through the intolerance of disagreement of any kind.” This philosophy encourages a victim-mentality that is then used as a trump card in ethical discussions about propriety and justice.

Respected evangelical leaders are actually promoting intersectionality as an appropriate way for Christians to identify themselves. Fortunately, other respected leaders are warning against it. [Note: the first linked article, by Jarvis Williams, can only be accessed on the Wayback Machine because it has recently been removed from The Witness (formerly RAAN). If this indicates a change of opinion by the author, that would be a welcome development and I would hope some statement indicating that would be forthcoming.]

The Bible never encourages believers to see themselves in terms of multiple victim-statuses. Does that mean that Christians are never victimized? Of course not. What it does mean is that the oppressions that come against us must never be allowed to identify us. We may well experience tribulation, distress, persecution, famine, nakedness, danger, or sword. In fact, for Christ’s sake we may be killed all the day long and regarded as sheep to be slaughtered. How then should we identify ourselves? As victims? Not according to the Word of God “No, in all these things we are more than conquerors through him who loved us” (Romans 8:35-37).

The Bible tells us what our identity in Christ is. If we truly believe it and believe that it is sufficient to inform us how to think about ourselves and others, then we will not fall prey to empty philosophy of intersectionality. That, in turn, will save us from finding any virtue in being “more victimized than thou.”

I will have more to say on the sufficiency of Scripture in future articles.

Follow Tom Ascol:

-

- Twitter | @tomascol

- Facebook | @tomascol

- Instagram | @thomasascol