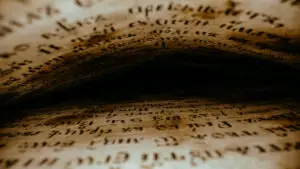

The book of Job consists of waves of expressions that indicate a desire for and the necessity of divine revelation for true knowledge. The entire book is a plea for knowledge from God. God cannot be known if he does not speak and his ways and purposes remain a mystery until he speaks. We find this expressed in several key points in the progress of the discussion in Job.

Something totally unexpected happened to Job. Having conducted himself with punctilious religious observance (1:5), purity (31:1) compassion, generosity (29:12-16; 31:16-23), and wisdom (29:7-11), he finds himself under a severe scourge-“God has cast me into the mire, and I have become like dust and ashes . . . You have turned cruel to me; with the might of your hand you persecute me” (30:19, 21). Though clear on the sovereign prerogatives of God (26:7-14), Job declares that God “has taken away my right” (27:2). Job was desperate for a word from God. He knew he could not understand his situation apart from God’s meeting with him. “Why is light given to a man whose way is hidden,” Job asked, “whom God has hedged in?” (3:23). Only God knows. “Let me know why you contend against me” (10:2).

Why God sends suffering to the lives of saints calls for revelation. Zophar knows that the answer to Job’s protests lies in the mind of God himself: “But oh, that God would speak and open his lips to you, and that he would tell you the secrets of wisdom.” It becomes clear that Zophar believed that such revelation would reveal a peculiarly deep guilt and hypocrisy on the part of Job. Job’s call was for a revelation as to why the innocent, godly, sincere, and compassionate are put to the test in such sufferings. Dealing with the ways of God with men calls for a wisdom that dwells only in the mind and purpose of God. The way to understanding is “hidden from the eyes of all living” and only “God understands the way to it, and he knows its place” (28:21, 23). If sin lies at the basis of Job’s suffering, he asks for a revelation from God of it: “Let me speak, and you reply to me. How many are my iniquities and my sins? Make me know my transgression and my sin” (13:22, 23). Elihu affirmed that only by revelation from God could the entire situation and questions surrounding Job’s suffering be resolved: “It is the spirit in man, breath of the Almighty, that makes him understand. . . . God speaks in one way, and in two, though man does not perceive it, in a dream, in a vision of the night” (32:8: 33: 14, 15).

In the midst of a desire for revelation of God’s purposes, we find that the language of Job is a marvel of revelatory inspiration. Several speeches manifest the Romans 1:19-21 grasp of revelation in that God’s power of creation and his control of nature in its every particular is affirmed. The moral implications of such power and wisdom are extended into the ongoing discussion—both sides of the encounter seek particular applications. In the narrative of these observations and arguments, we find some of the most picturesque and striking linguistic images in all of literature. It is not just a literary triumph, but the substance implied behind the images gives powerful insight into the ways and wisdom of God, laying the foundation for Paul’s revelatory affirmation in Colossians 1:15, 17, “By him all things were created, . . . and in him all things hold together.” Elihu expressed the dependence of all creation on the initial creative power of God and his continual and immediate operation of sustaining: “He covers his hands with the lightning and commands it to strike the mark. . . . By the breath of God ice is given, and the broad waters are frozen fast. He loads the thick cloud with moisture; the clouds scatter his lightning” (36:32; 37:10, 11). Job emphasizes his sense of utter despair and helplessness by comparing himself negatively to a dead tree: “For there is hope for a tree, if it be cut down, that it will sprout again, and that its shoots will not cease. Though its root grow old in the earth and its stump die in the soil, yet at the scent of water it will bud and put out branches like a young plant. But a man dies and is laid low; man breathes his last, and where is he?” (14:8-10). Also, we find beautifully crafted language in service of a plain expression of the central moral issue involved, another point of revelation given in conscience (Romans 1:32; 2:15). “God is clothed with awesome majesty. The Almighty–we cannot find him. He is great in power; justice and abundant righteousness he will not violate” (37:22, 23).

As the interchange proceeds and becomes more sarcastic and acerbic, we find the necessity of revelation to clarify the assumptions of both sides of the contest. The friends hold some propositions that are true but apply them in a wooden way as if the immediate manifestations of this present life will perfectly consummate God’s displays of both justice and reward. They are careless in their examination of the phenomena involved—Job is quick and thorough in pointing that out (21:29-34)—and are unfailingly confident in their applications of general principle. They fail to recognize that further revelation would unveil some of the mystery that surrounded Job’s wrenching dilemma. God said that the disasters were “without reason” (2:3), that is, without any particular act of outrage or injustice to provoke immediate divine reprisal, but Job’s friends increase throughout the book in the certainty of their knowledge of the “reason” that calamity invaded the life of Job. Applying the true principle of punishment for sin and life for righteousness, Eliphaz instructs Job, “If you return to the Almighty you will be built up, if you remove injustice far from your tents” (22:23). In a particularly vicious speech against Job, Bildad said, “Shall the earth be forsaken for you? [Will the immutable principle of iniquity-brings-judgment be suspended because of your complaints?] . . . Indeed the light of the wicked in put out . . . He is thrust from light into darkness, and driven out of the world” (18:4, 5, 18). Zophar used graphic language in his obvious disdain for Job’s contention of innocence: “He will suck the poison of cobras; the tongue of the viper will kill him . . . a fire not fanned will devour him; . . . This is the wicked man’s portion from God” (20:16, 26, 29).

Throughout all these, and more, Job was in a state of resistance to their “empty nothings” (21:34). “Surely there are mockers about me, and my eye dwells on their provocation” (17:2). He assaulted them with sarcasm (“How you have helped him who has no power! How you have saved the arm that has no strength!”). His clear-headed and determined rejection of their extrapolations of principle did not solve the mystery. He addressed God, “I cry to you for help and you do not answer me” (30:20). He knew that wisdom to discern the meaning of the ways of God with man lay in the deep recesses of God’s mind: “God understands the way to it, and he knows the place” (28:23). Job knows that God has given a summary of all wisdom that should prevail in every situation: “And he said to man, ‘Behold, the fear of the Lord, that is wisdom, and to turn from evil is understanding’” (28:28).

Job’s struggle led him into a provocative engagement with the justice and goodness of God. By an infusion of the Spirit with his reasoning, Job, and to a greater clarity Elihu, came to set forth the need for a ransom. This revelation came through reasoning from settled truths and a particular existential situation to a proposal consistent with both. God is just and will not compromise the standard of absolute righteousness as the qualification for eternity in his beneficent presence. Throughout the discussions and recognized perplexities, therefore, we find real advances in revelatory truth that prepares for a more comprehensive grasp of gospel realities. Job had asked, “If a man dies, shall he live again?” (14:14). In the gargantuan struggle with the seeming meaninglessness of righteous-living in the face of God, with the specter of suffering pressing him more harshly every moment, he edged forward with a confident assertion of something apparently revealed: “Oh that my words were written! Oh that they were inscribed in a book! . . . For I know that my Redeemer lives, and at the last he will stand upon the earth. And after my skin has been thus destroyed, yet in my flesh I shall see God, whom I shall see for myself, and my eyes shall behold and not another” (19:23-27). And indeed, they were written! This came as a further manifestation of revealed insight that had been stated in 16:19-21: “Even now, behold, my witness is in heaven, and he who testifies for me is on high. My friends scorn me; my eye pours out tears to God, that he [my witness] would argue the case of a man with God, as a son of man does with his neighbor.” By the secret and painful operations of God’s revelation, Job knew that he must have one who was in sympathetic harmony with man and ontologically identified as man but could speak familiarly with God. Elihu provided another step of revealed truth wrought in the context of this heaven-ordained turmoil. “If there be for him an angel, a mediator,” Elihu proposed, “one of a thousand, to declare to man what is right for him [the revelation of the just way out of the experience of wrath] and he is merciful to him, and says, ‘Deliver him from going down into the pit;’ [He has delivered us from the domain of darkness] I have found a ransom.” Certainly, the Son of Man came to give his life a ransom for many.

When the Lord himself confronts Job with the impertinence of his resolute confidence in his ability to question God and provide succinct and credible answers to him, he provides no answer other than the magnificence of his presence and the impenetrable nature of his doings. Job understands the series of questions and concludes that indeed he “hides counsel without knowledge” and uttered what he did not understand. The experience brought renewed perspective to Job and changed his insistence into repentance. God told the three friends “You have not spoken of me what is right, as my servant Job has.” Job’s resistance to their incorrect and simplistic conclusions was right and, by revelation, his knowledge that he needed a mediator who could plead his case was an insight to be fulfilled only in the incarnation of the Son of God.